In Memoriam:

Franz Clouth (1838 - 1910)

Venture

Business

Freedom

(of decision and action)

Sucess

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

|

In Memoriam:

Franz Clouth (1838 - 1910)

______________________________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

Old Clouth firm Logo

Altreifen

Balloon Gondola

Cöln Beginning of 20 Century.

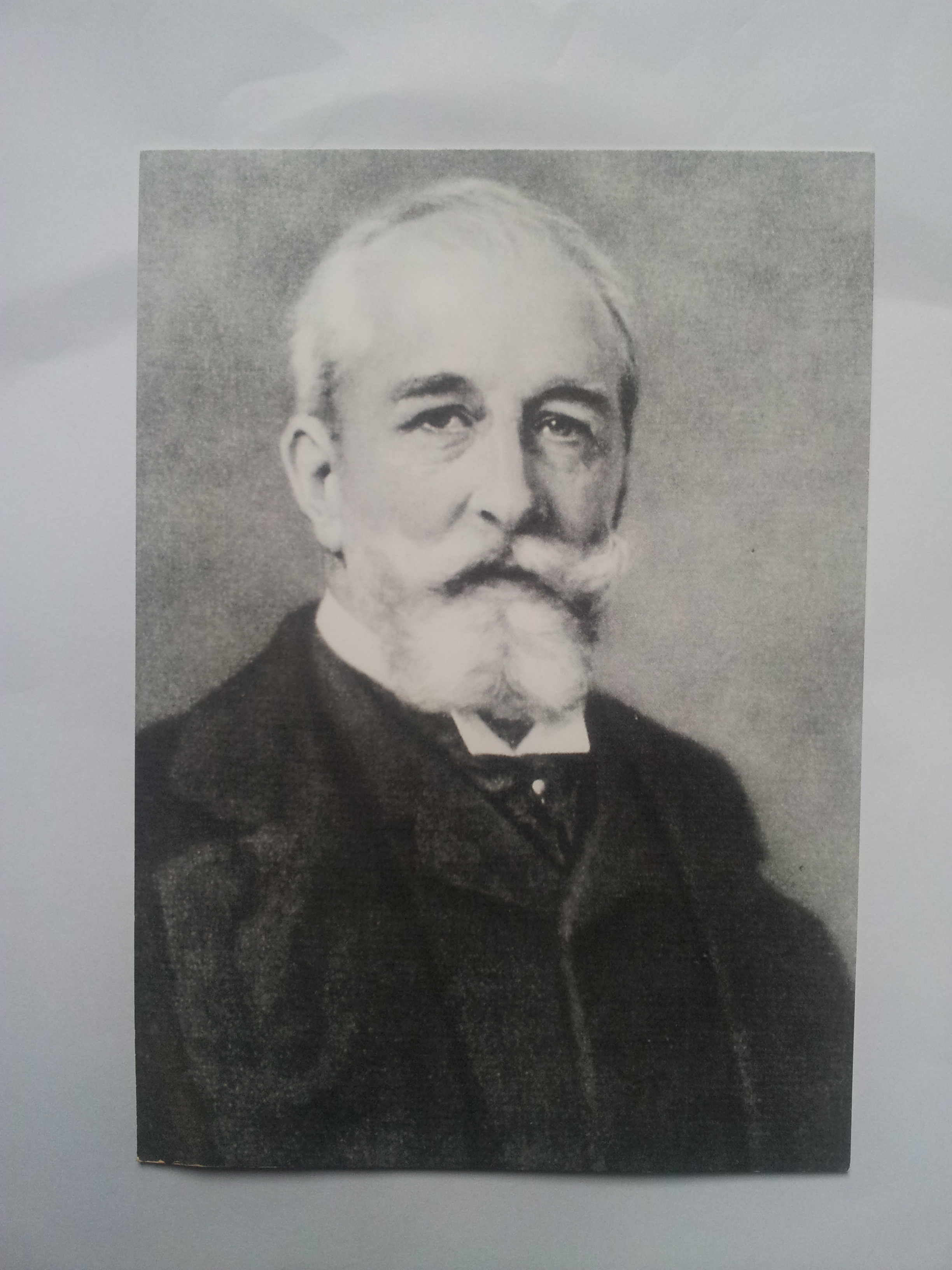

Franz Clouth

Bronze F. Clouth Bust

Clouth Book Nr.1

Diving Helmet Clouth

Clouth-Wappen 1923

Clouth Balloon XI

Rechtsanwalt J.P. Clouth

Ehefrau Audrey Clouth

Bryan, Oliver, Phillip Clouth

Max Clouth

Clouth Balloon Sirius

Kautschuk Golfball

Clouth Factory Front

Younger Franz Clouth

Eugen Clouth

Clouth Factory

Air Ship Advert

Clouth Money

Old Clouth Crest

Car tyres

Old Car

OLd Daimler

Excavator with conveyor belt

Clouth VIII Balloon

Wilhelm Clouth

Katharina Clouth

Caoutchouc Golfball

Draft of Clouth Memorial

Old Catholic Church Köln

Cable Tower

Clouth IX

Ticket for Clouth IX Drive

Clouth IX

Clouth Buch 2.Edition

old Franz Clouth

Balloon Gondola

Butzweilerhof Airport

Caoutchouc-Tree

Caoutchouc Sheets

Caoutchouc-Copy Mashine

Water-Regulator

old Land & See Logo

Land & See New logo

Franz Clouth

Richard Clouth

Industrieverein Altlogo

Conveyor Belt Hall

Gate 2 to Clouth Works

Atlantic Cable

von Podbielski Cable

Layer

Sound Silencer "Clouth Ei"(Egg)

Printery Wilhelm Clouth

|

Cables

submarine cable

The first attempt to lay a cable between Great Britain and America took place in the years 1857 and 1858. While good experiences with coastal cables could be used, the cables laid across the Atlantic were, however, unusable after only a few business weeks, as Wildman Whitehouse used too high voltages during operation. It is assumed that the cable would not have had a long life due to insulation problems that were caused by the manufacturing and handling of the cable. [1] Ten years later, however, better insulated cables were available, which reached a significantly longer service life. So-called spooled cables in the form of sea cables were used. In 1865 a new transatlantic line was laid by the steamboat Great Eastern. But the cable tore 600 miles off the coast of Newfoundland and could not be recovered. Between July 13 and 27, 1866, another cable was relocated by the Great Eastern and put into service on July 28, 1866. The cable section, which was laid in 1865, could also be recovered and supplemented by the missing piece. [2] In 1874 the Faraday moved the first transatlantic telegraph cable for the Siemens brothers Wilhelm and Werner von Siemens, which was operational until 1931. In 1900 Germany also had not only lines in the North Sea and Baltic Sea with a total length of 4180 kilometers, but also a transatlantic cable, which had been produced in England (Siemens GB) for the German Atlantic Sea cable company and laid 1904 from Emden (East Frisia) via the Azores Island Faial to Coney Island in New York. Details of Clouth Cable:

In 1919, the number of operational transatlantic cables had grown to 13, mainly in British ownership.Sea cables for the transmission of energy are no longer suitable for the transmission of conventional three-phase alternating current from about 70 km long, then the more complex high-voltage direct current transmission (HVDC) has to be used.

At that time the area of the big economy was still unobtainable to the individual. As a rule, many entrepreneurial figures knew each other, Franz Clouth was a member of early Rotary connections, an economic club that was still in its early stages. He also had decisive contacts, but also with regard to the international foreign countries through congresses, organized meetings in domestic fairs, worldwide trade fairs he had his own connection with the size of economics. In addition, there was family contact with Krupp in Essen in Germany. Dangers from certain areas of the economy were very fast. This is where the liability of the company and its own company always came into its own, at Clouth, with the legal advice to enter the economically risky route of the production of sea cables through an independent company, to exclude liability and regression at the expense of Clouth.

The laying of a transatlantic cable does

not come out on a whim, requires a thorough preliminary planning. Already at the

shift of the first, Clouth moved the fifth, there had been considerable

difficulties, for example cable cracks halfway, weather-related damages, huge

costs. In addition, a

With this "Podbielski" cable ship, Norddeutsche Seekabelwerke, which came out of the "Land- und Seekabelwerk AG" in 1904, laid an almost 8,000 km-long communication cable from Borkum across the Azores to New York. That Franz Clouth has thought of this proves his previous entrepreneurial strategy in Cologne.1889 he had made the necessary land acquisition for the extension of the factory site for the purpose of cable manufacture. Between May and July 1890 the purchases of a transmission, a Wollf locomobile (a locomotive (locomotive, locomotive, locus and mobilis: mobile), now sometimes also called locomobile (neutral) was a steam engine installation in a closed design, in which all assemblies (combustion, steam boiler, control and the entire drive unit, consisting of cylinder (s), piston, crankshaft and flywheel with belt pulley) required to operate the system were mounted on a common platform) as well as a rope hammering machine. At the beginning of June 1890 the cable manager Lukas of the Siemens Brothers, London, took over the service of Franz Clouth. A little later an engineer, an inspector, and a worker were hired. Also a special construction engineer. This built a much needed lead pin. Finally, in November 1890, the first wires could be made. (According to M. Backhausen / "Life in Nippes, work at Clouth)

What Backhausen described as "strange

blossoms of a mixture of Clouth and cable works" thus constituted a legal

balancing act, which the two companies should at least have to face outwardly at

the time, in such a way that they could not be regarded as the same legal person

under legal l Important is the reference in the above-mentioned book to the "senior engineer" to which Georg Zapf was appointed in September 1891. Zapf was previously assistant to Oskar von Miller (1855-1934) one of the pioneers of the German electricity industry. He was co-founder of the AEG and founded the Deutsches Museum in 1903 in his hometown Munich. Whether Franz Clouth had actually met Zapf at the electrotechnical exhibition in Frankfurt, Main, did not exclude previous contacts. Franz Clouth was also integrated internationally in the electrotechnical sector. The exploration of electricity and its practical application was at that time an essential condition for factory survival and so for company owners, if they wanted to keep pace with the rapid economic and scientific development, so this was a question of existence. Land and Sea AG productions were later about 1904 connected to Felten & Guilleaume, Köln (see "clouth book") because 1925, Felten & Guilleaume became the main shareholder at Clouth.

Transatlantic cable

"Like a ladder to the moon" In summer 1866 private entrepreneurs cable the Atlantic between Europe and America and accelerate trade and communication. It is the beginning of a new epoch in which the world is radically transformed. The American entrepreneur Cyrus W. Field declined in 1854 a more than ambitious idea: he wants to lay a telegraph cable across the North Atlantic, between the west coast of Ireland and the Canadian Newfoundland. This is intended to speed up communication radically for trade and political exchanges between Europe and North America. The millionaire is supported by some of his rich neighbours from Gramercy Park, a district of New York. With Samuel F. B. Morse Field wins one of the inventors of telegraphy as a consultant. Together they establish the New York, Newfoundland and London Telegraph Company. For a long time the men around Cyrus W. Field stand apart from the political and scientific establishment. Many smile at her. Their idea of laying a telegraph cable across the rugged North Atlantic sea, the Steward of the cable ship Great Eastern, recalls many times in the middle of the nineteenth century, "as crazy as the proposal to build a ladder to the moon" 1.800 nautical miles should bridge the cable, which is more than 3,000 kilometers. Above all, from a technological perspective, the Atlantic cable project is an extremely risky undertaking. Little was known about the seabed and the currents occurring there. The cable publishers had to rely on the controversial statements of the American oceanographer Matthew F. Maury, who wanted to discover a transatlantic plateau between Ireland and Newfoundland in 1853: only two nautical miles deep, without significant trenches and also low in flow. This plateau, writes Maury in a letter to Field, was "intended to lay down a deep-sea cable". The British and American governments are reluctant to say their support for the project. Marine units of the two countries undertook several surveys in the years 1856 and 1857. They did not provide certainty about the results of Maury.

Between 1857 and 1866 the project is an expensive series of failed attempts. The enterprises can only be safely carried out within the short time between spring and autumn storms. At the first attempt in 1857 the cable still breaks on the day of departure from the west of Valentia Island. Although initially raised, it was irretrievably lost a few days later. In 1858, the Atlantic crossing succeeded. But because one mistakenly believes that the signal transmission works the better, the more current is used, one of the two chief engineers sends such high volts through the cable that in the end only a mangled piece of wire remains on the ocean floor. Between 1861 and 1864, the turmoil of the American Civil War prevented further ventures. Urgently necessary new investors frightened the previous failure rate. The rescuer in need is John Pender, a textile contractor from the north of England who, in 1865, puts a large part of his private assets in the Atlantic cable and initiates important company reforms. But happiness is not at first given to him either. 1865 the cable breaks again at sea. With each failed attempt, the cable crew sunk nearly 200,000 pounds, on today's scale a sum in the multi-digit million range, at the bottom of the sea. They do not think of giving up. Like many of their contemporaries, they are convinced of the controllability of nature and animated faith in technology and progress. On July 27th, 1866, exactly 150 years ago, it happened. "Suddenly he broke loose, the storm of rejoicing, and they all jumped into the water, screaming their happiness and relief as loudly as if they wished they were still being heard in Washington our sailors held the cable up and danced wildly around it, one of them even in the mouth, I felt no different, shouting loudly as she did, and only wanted to cry softly, we had made it. " With these lines, Sir Daniel Gooch, British railroad and telegraph engineer, recalled his diary records on July 27, 1866. The day after nearly four weeks at sea, in the middle of nowhere, the coast of Newfoundland was reached with a crew of English, Irish, and American engineers , Electricians and seafarers. The newspapers are enthusiastic about success. "The Eighth Worldunder", "A Pledge of Love Between Age and New World," "An Anchor of Hope," are the headlines. Some people even believe that it is now possible to build a world-wide cable network, which not only promotes trade and diplomacy, but also leads to world peace. Any international misunderstanding, as Emperor Napoleon III, for instance, is now swarming with a telegram.

You can see the "beginning of a new age" in the event the german writer Stefan Zweig celebrates the Atlantic cabling later in his collection of the hours of the hours of mankind, which shine "glowing and unchangeable as stars over the night of transience". According to the British historian Gillian Cookson, generations of historians also recall the "cable that changed the world". Soon, other cables will extend from Europe to India, Southeast Asia, Australia, Latin America and South Africa. At the same time, governments are continuing to expand their land telegraphy. At the end of the 1870s, almost every trading center can be reached from Europe by telegraph. The maritime cable network covers between 70,000 and 100,000 kilometers.

Transatlantic cable The cable

Land & Sea later Nordenham Felten & Guilleaume

single Cable production cable interweaving

Inside,

copper wires are interwoven, which have been protected by a gutta-percha

insulation and an additional covering. The diameter of the cable is

In the following decades, popular connections are doubled and triple. By 1900 alone, twelve sea cables crossed the Atlantic. Technical innovations such as duplex and later quadruplex telegraphy allow simultaneous sending of two or four messages from both ends of the cable. In 1869, by the Atlantic cable only 321 messages a week had gone, the Atlantic network 1903 processed approximately 10,000 messages daily. About 406,000 kilometers of sea cables span the globe. No wonder the operators are among the most lucrative and successful multinational companies of their time. The sea telegraphy changed the world at that time from the ground up. Information is dematerialized. In the speed of its transmission it is no longer bound to the speed of the deliverer. Contemporaries are enthusiastic about a "dissolution of time and space": If a letter by steamboat had been traveling for almost two weeks to cross the Atlantic, the crucial information can now be transmitted in a few minutes. The world is 1866 on the direct way to the global village.

Telegraph In the following years, small telegraph stations are often set up on the spot where guests can spend an evening in the wide world - free of charge. The next morning, a transatlantic telegram of 20 words costs up to 20 pounds, which is more than the week's income of a simple craftsman. Although tariffs fall to just a few cents per word in the first three years, transoceanic telegraphy remains the communication medium of a very small, white, western and male elite by the early 20th century when it is replaced by wireless telegraphy Wealthy private individuals, entrepreneurs, journalists and politicians. This elite is using the sea telegraphy for the continuous training of economic, political, and cultural and social networks all over the world.

The cable becomes the basis of modern capitalism As a private company the sea telegraphy is officially neutral. It merely connects the respective nations and continents. At the same time, sea cables and imperialism, especially the British one, are not separately conceivable. Entrepreneurs follow colonial power and trade routes in cable laying and profit from free access to natural resources such as gutta-percha from the British Empire. Imperial Powers use the sea cables to at least make the feeling of stronger control over their colonies. For a good reason: the Indian uprising of 1857 against the British colonial rule left the memory of impotence. The call for help from General Sir Henry Lawrence to evacuate all Europeans "from the subcontinent as quickly as possible" took 40 days to reach London. At the same time, the opponents of the Empire strive to use the telegraph network against the political establishment. Irish nationalists have tried to occupy the transatlantic cable stations until the 1870s. The Indian national movement around 1900 used the telegraves to organize themselves against the British. And not for nothing does the Spanish government at the same time have the telegrams inscribed into insurgent Cuba not in code. Ultimately, the sea cables, such a contemporary, are "instruments on which every melody can be played." No one speaks of world peace by sea telegraphy.

Cable coiling

Journalists are pushing the question, which is considered interesting at the other end of the cable. Already in October 1866 came from the European side first complaints that the news from America are neither very new nor interesting. In London, a journalist from the British tradition sheet Spectator is indignant at being informed of the death of a certain John van Buren, of whom no Englishman ever heard: "Where were the election results from Ohio and Pennsylvania, or at least the stock exchange information?" It was not until the late 1880s that the telegraph code was so widely developed that it was possible to quickly clarify the communicative misunderstandings of John van Burens, the son of the former American president. As a result of the costs, a telegram style is established, which even penetrates the literature. The Swedish writer August Strindberg writes in his essay What is the "modernity"? In the year 1894: "The art of writing letters from three sides is no longer necessary ... And the telegram is the ideal, only the name, and without title The naked facts, without phrases, form the text: Question And answer, 'Be assured, Sir, of my excellent conquest' (...). "In short, the Atlantic cable laid 150 years ago was the first puzzle piece in a global communications network, paving the way for world trade, world politics and the global public. Even today, despite satellite technology, more than 90 percent of the Internet traffic goes through the connections at the bottom of the world's oceans. The cables may be new, the routes are old.

Telephony and data traffic Wikipedia

In the first 24 hours, 588 calls were transferred between London and the United States, and 119 from London to Canada. The capacity of the cable was therefore soon extended to 48 channels. TAT-1 was finally switched off in 1978. The second transatlantic telephone cable TAT-2 was put into operation on 22 September 1959; The number of speech channels was thereby increased to 87 by the time-assigned speech interpolation (TASI) method; In this method, a channel is assigned to a subscriber only if it actually speaks. From 1963 on TAT-2 a semi-automatic telephone service between the Federal Republic of Germany and the USA could be offered. The coaxial cable TAT-3 was laid between 1963 and 1965; It ranged from Great Britain to New Jersey and had a capacity of 138 voice channels with a maximum of 276 voice connections and an amplifier spacing of 37 kilometers. TAT-4 was relocated in 1965 between France and New Jersey with a capacity of 345 voice connections; Two groups of speakers served to connect Austria with the United States. From 1968, Austrians were able to reach Canada through CANTAT. The 6300 km long TAT-6 followed in 1976 between France and the USA; It had over 4200 speech circuits and needed 693 repeaters at a distance of 9 kilometers. Deep-sea cables enable data communication over large distances and can transport data volumes that are larger than those of the strongest communication satellites. A further advantage over satellite connections is the significantly shorter running time of the signals. However, they share a great disadvantage with satellites: as well as satellites, such as satellites can only be modified, maintained, expanded or otherwise processed in a subsequent way. Above all because of the high data volume, deep se cables are used particularly frequently in the Atlantic between North America and Europe. There are only a few countries which do not yet have a connection to a high-performance message cable. Initially analogue electrical signals were transmitted. Meanwhile, strands of glass fiber cables lie on the seabed. A fiber-optic cable contains several fiber pairs, while the TAT-14 laid in the North Atlantic is four. Multiple data streams can flow at a time via a fiber pair through the so-called "multiplexing". Latest fiber pairs can well transfer a terabit data per second. The fiber optic cables lie in a copper tube, which is poured out with a water-repellent composite. Around this copper tube there is an aluminum tube for protection from the salt water, followed by steel ropes and, depending on the strength of the protection, several layers of plastic. At the same time, the copper tube serves as an electrical conductor in order to supply the optical amplifiers, which are inserted in distances (with modern cables 50-80 km), which are looped into the cable. The seawater serves as a return line for the operation of the amplifiers. The operating voltage reaches the order of 10 kV. In front of the coasts, more armed cables are used because of the rising sea floor and the associated risk of damage by ship anchors or fish trawlers. However, even these arrangements do not always help. On February 28, 2012, a ship waiting for a mooring in the port of Mombasa capped a subseekabel with its anchor and thus lamented a substantial part of the Internet connection of East Africa.

|

|

For questions

and comments please contact by

info@rechtsanwalt-clouth.de

|