|

Old Clouth firm

Logo

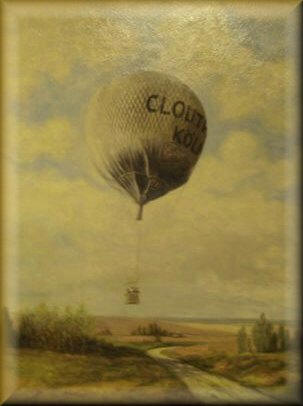

"CLOUTH"

Altreifen

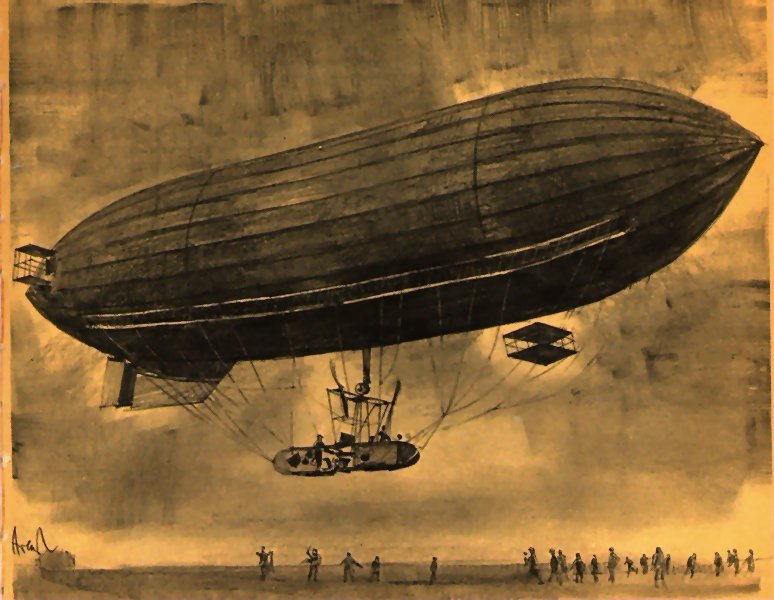

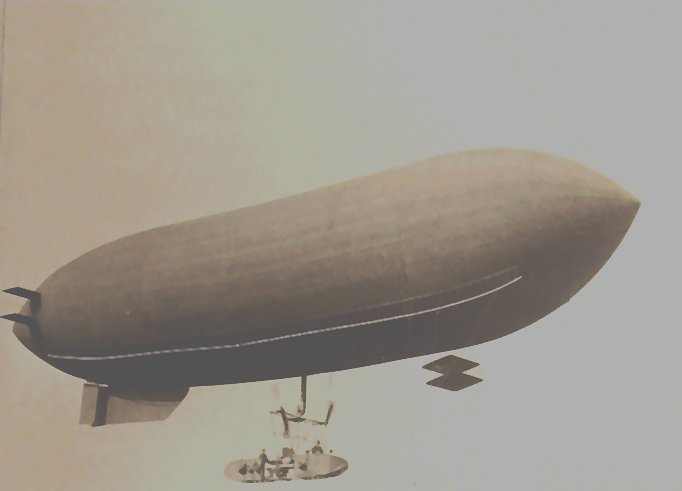

Balloon Gondola

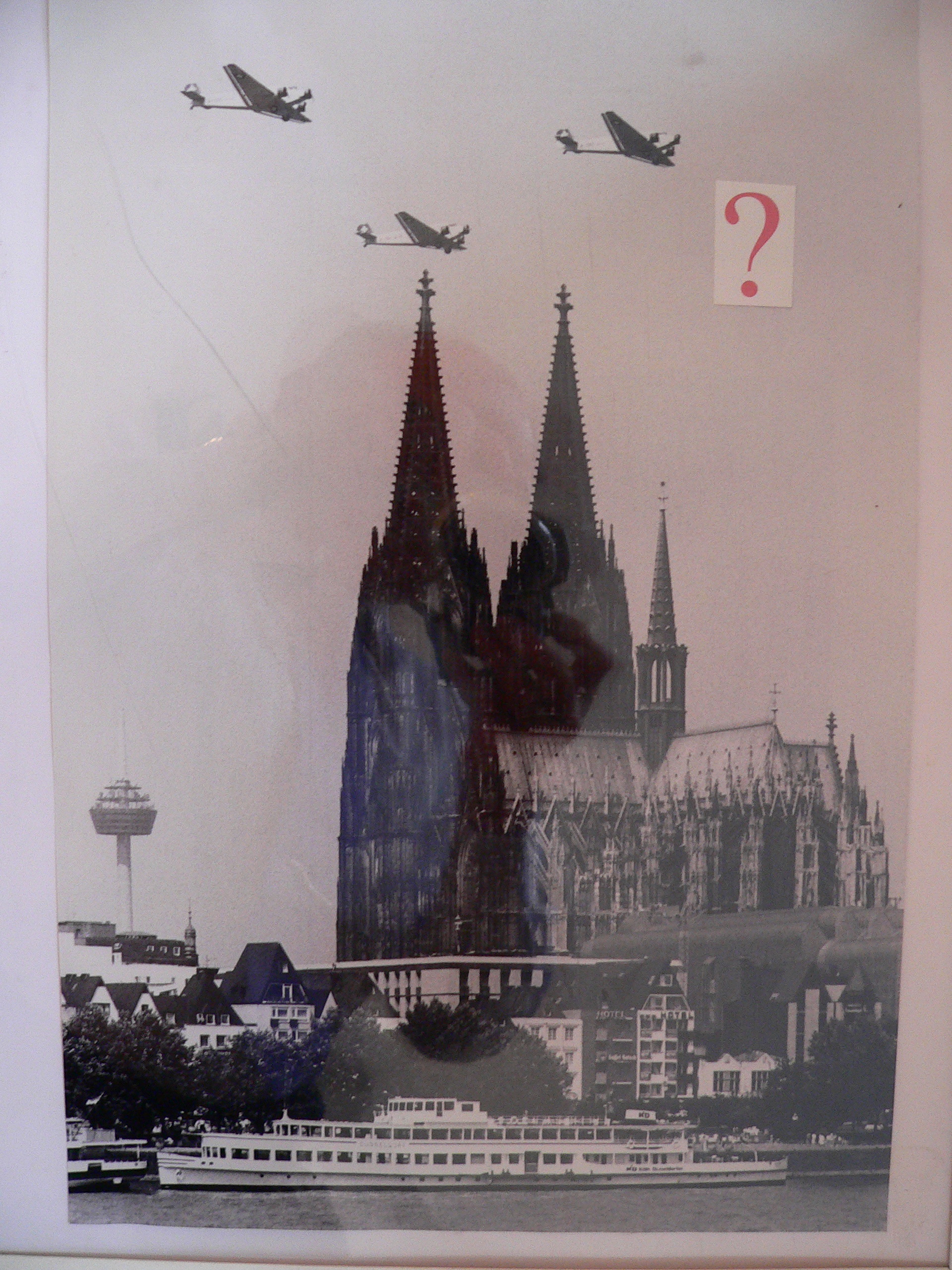

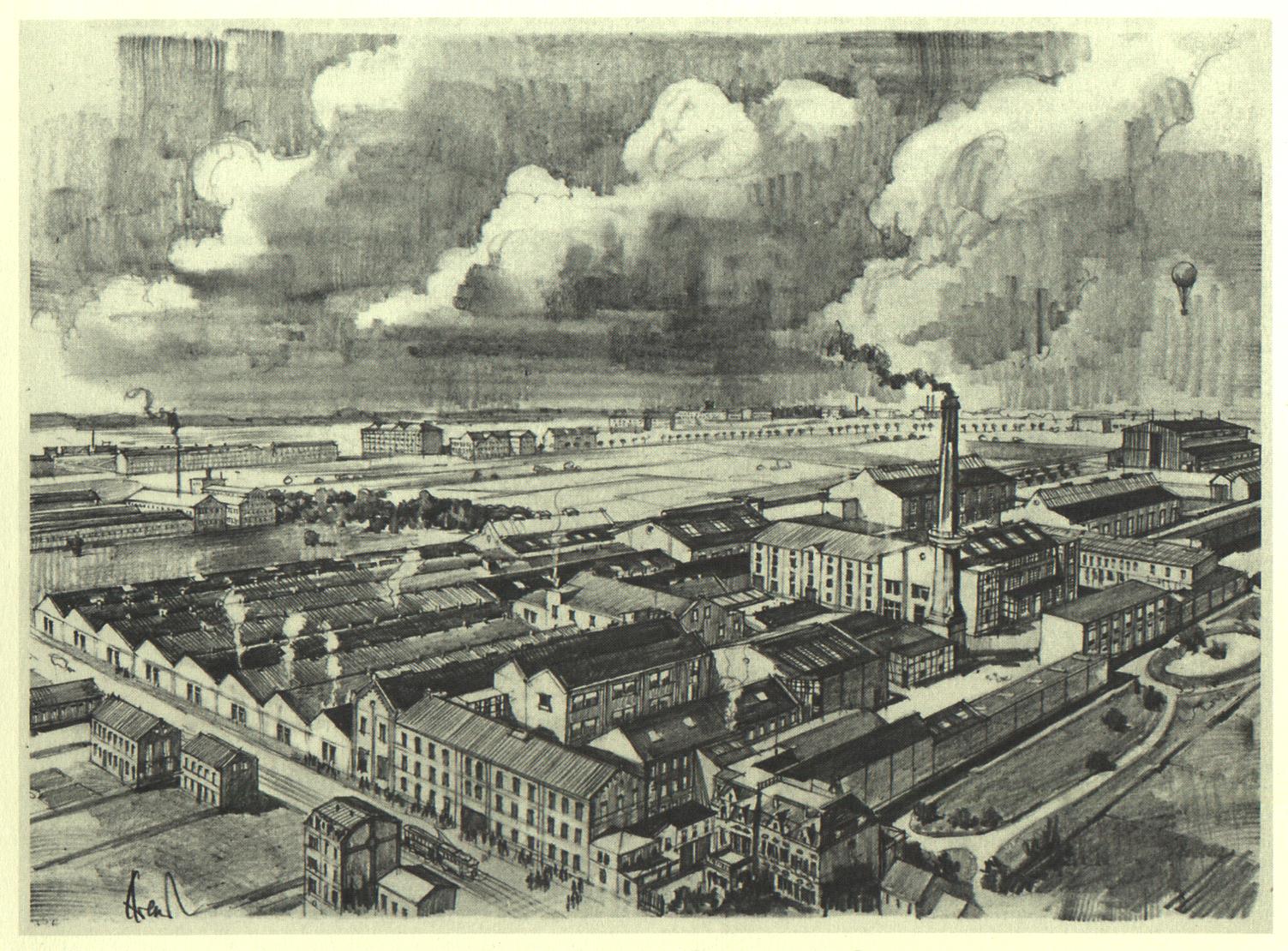

Cöln Beginning of 20

Century.

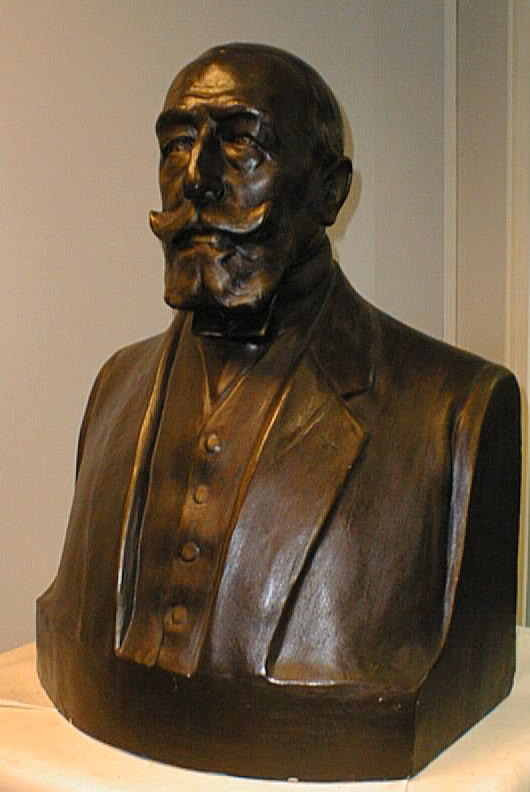

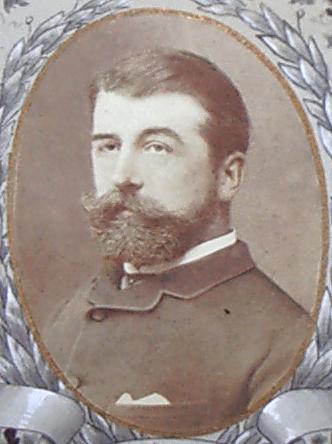

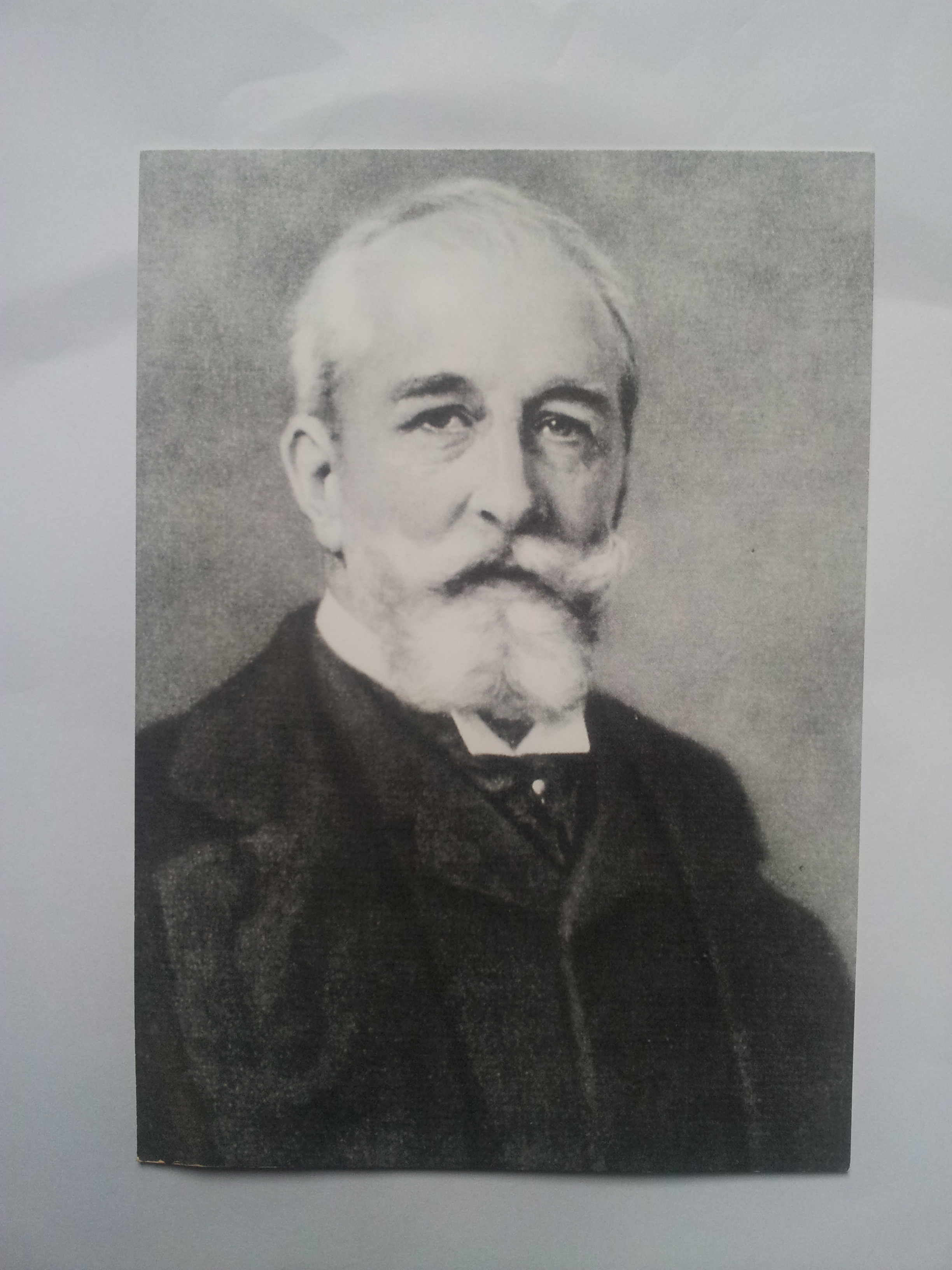

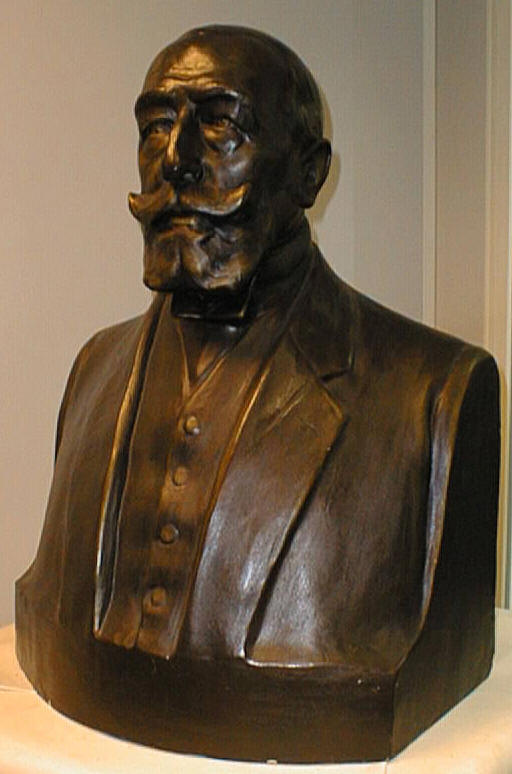

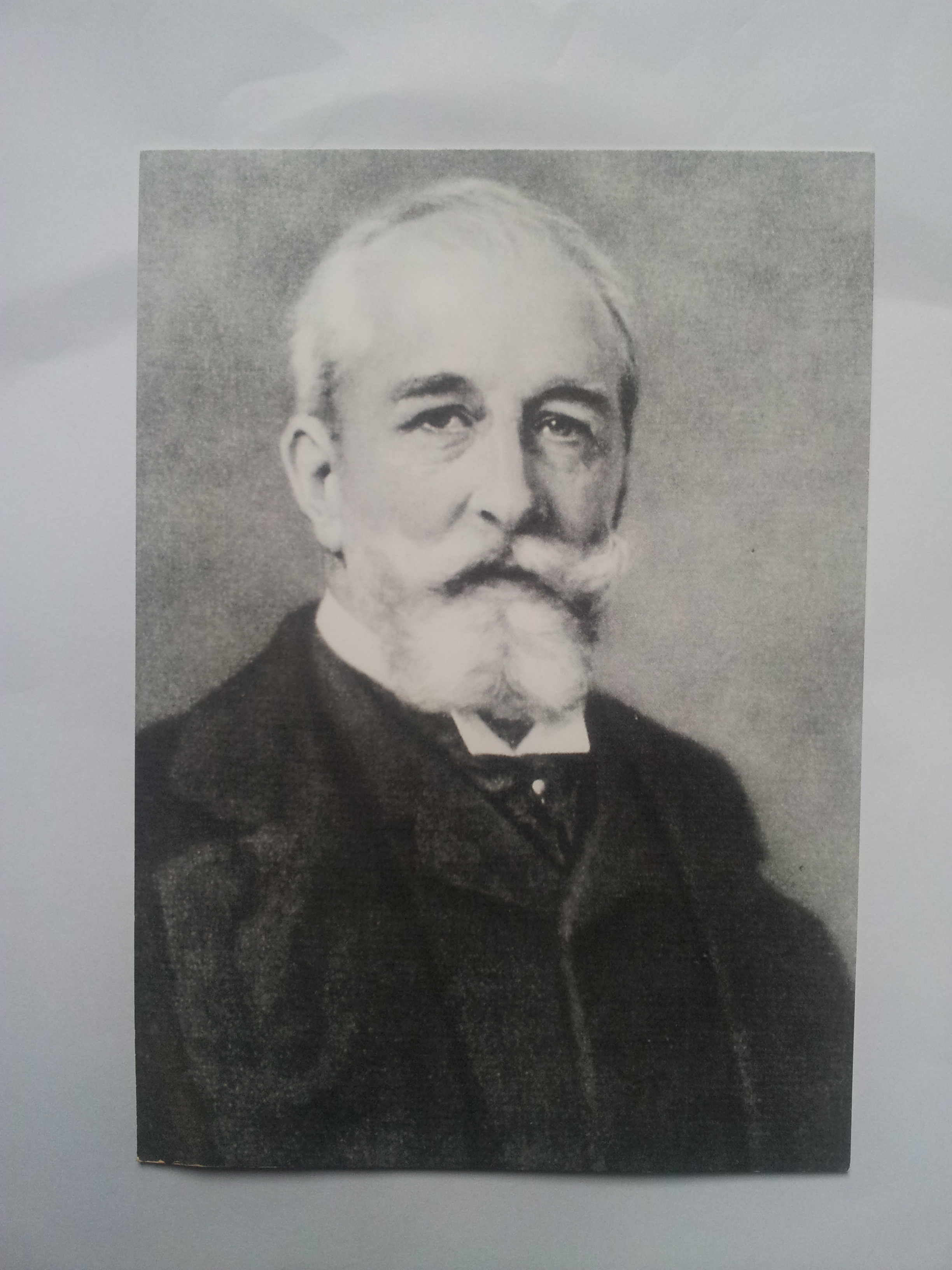

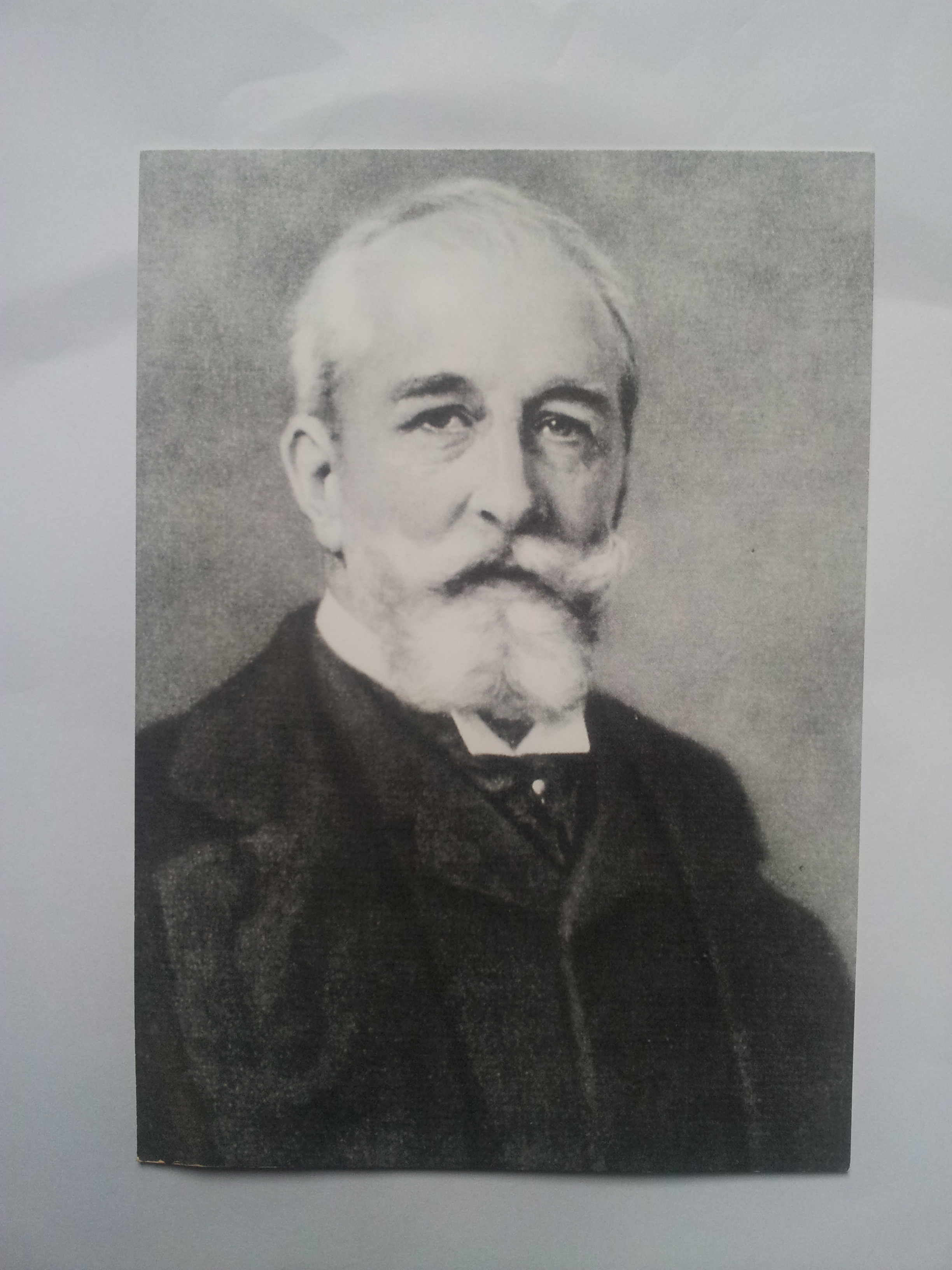

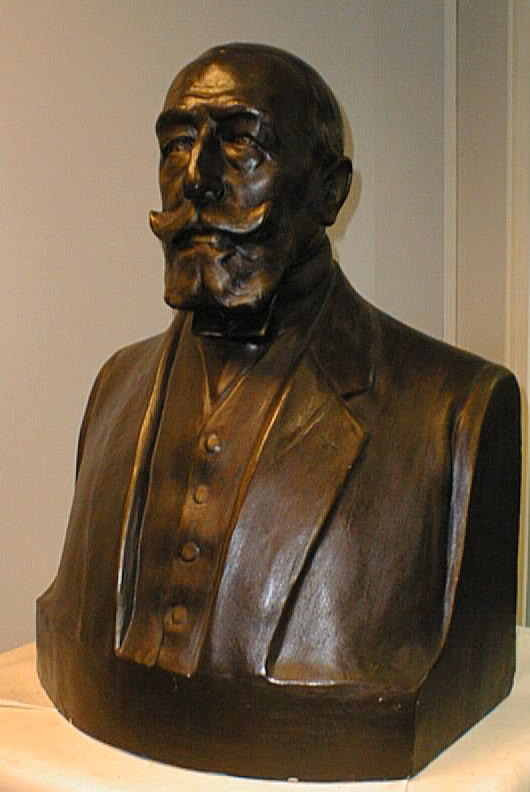

Franz Clouth

Bronze F. Clouth Bust

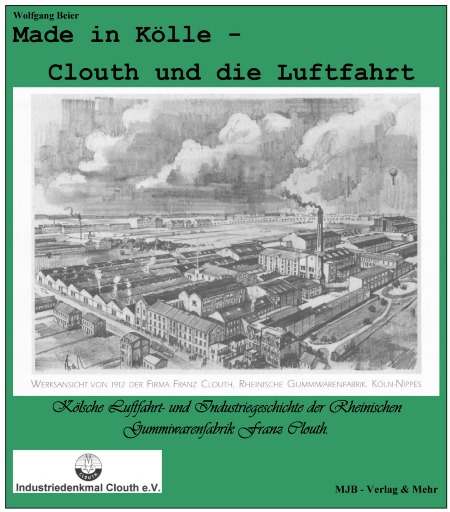

Clouth Book Nr.1

Diving Helmet Clouth

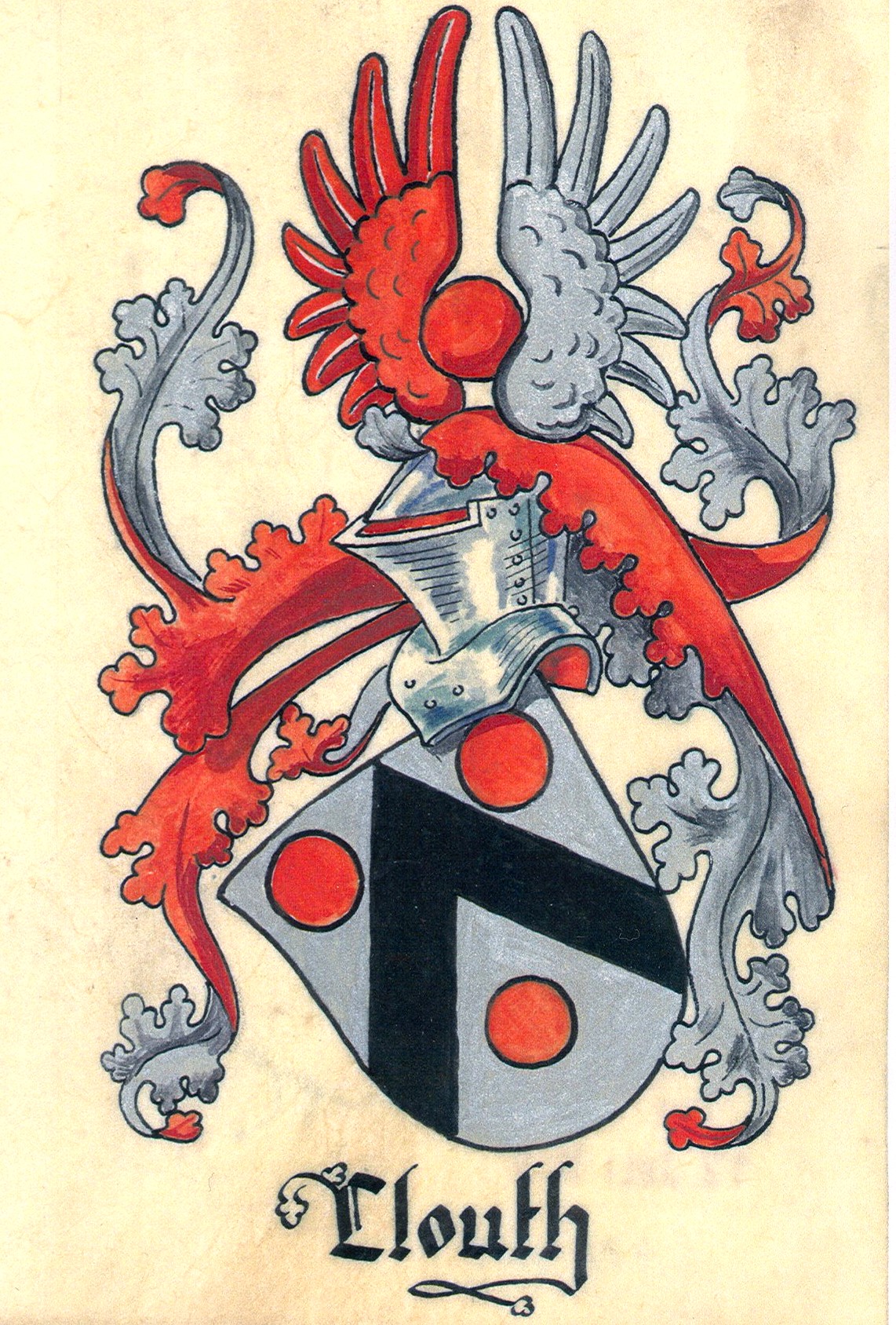

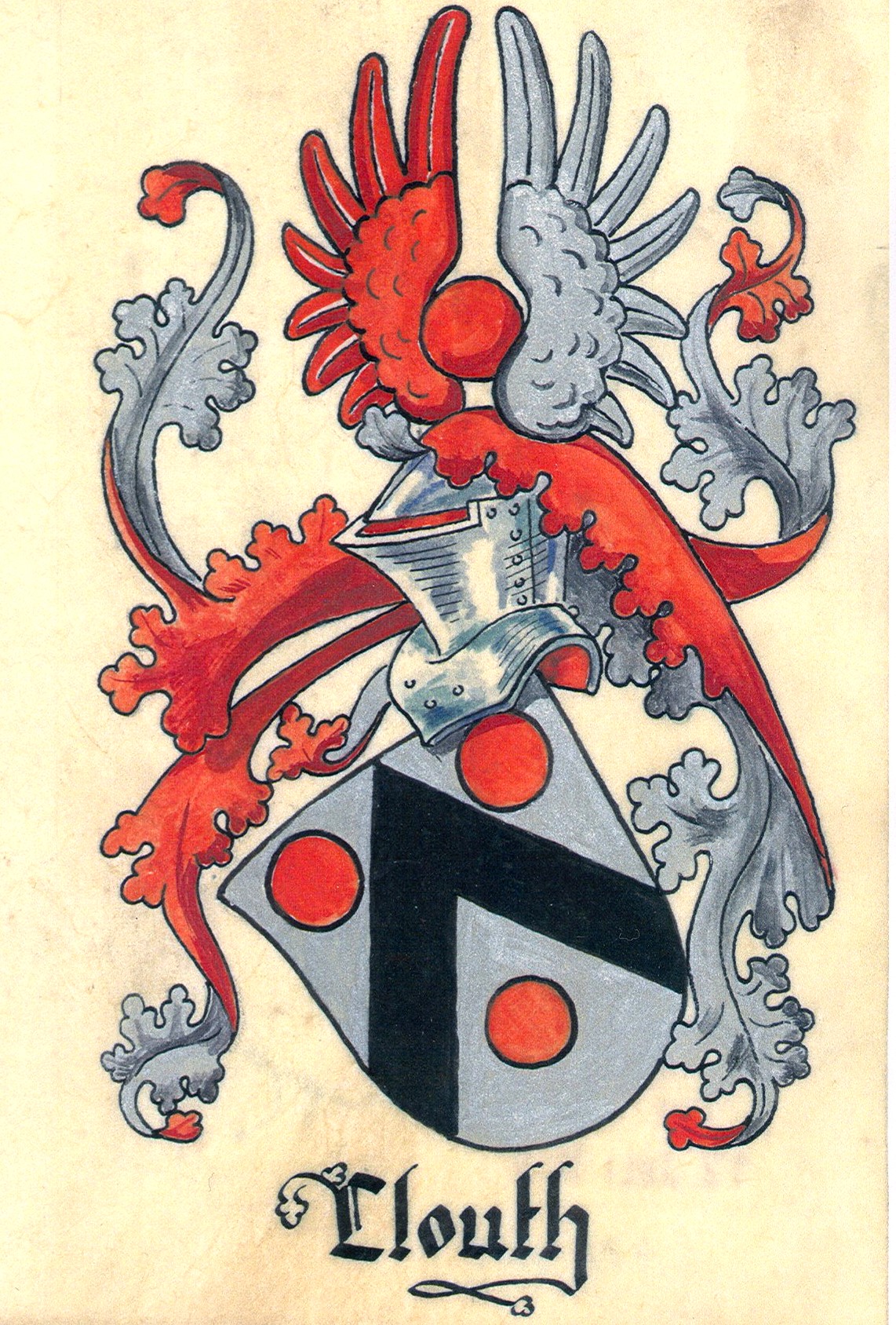

Clouth-Wappen 1923

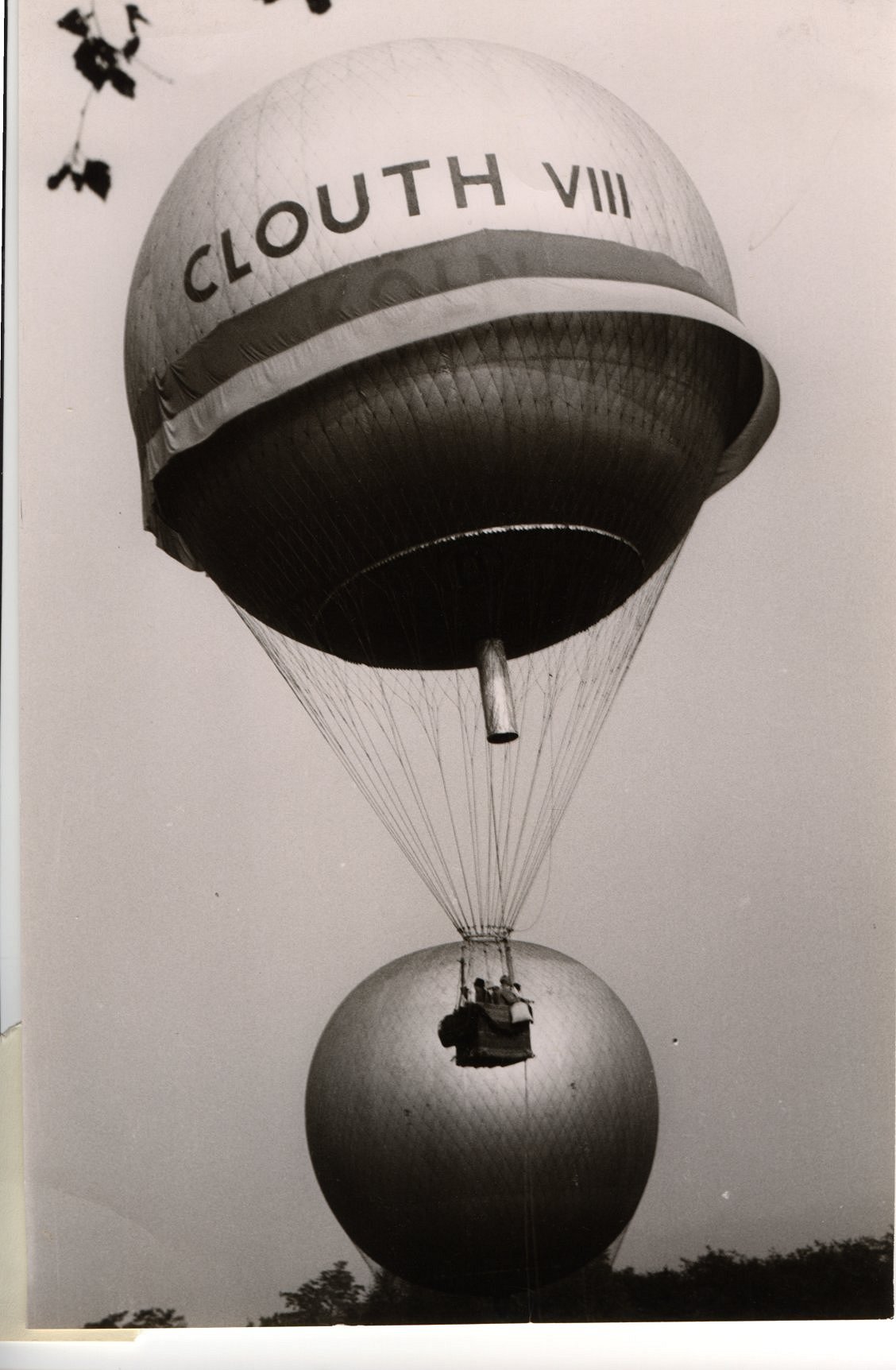

Clouth Balloon XI

Rechtsanwalt J.P. Clouth

Ehefrau Audrey Clouth

Bryan, Oliver, Phillip

Clouth

Max Clouth

Clouth Balloon Sirius

Kautschuk Golfball

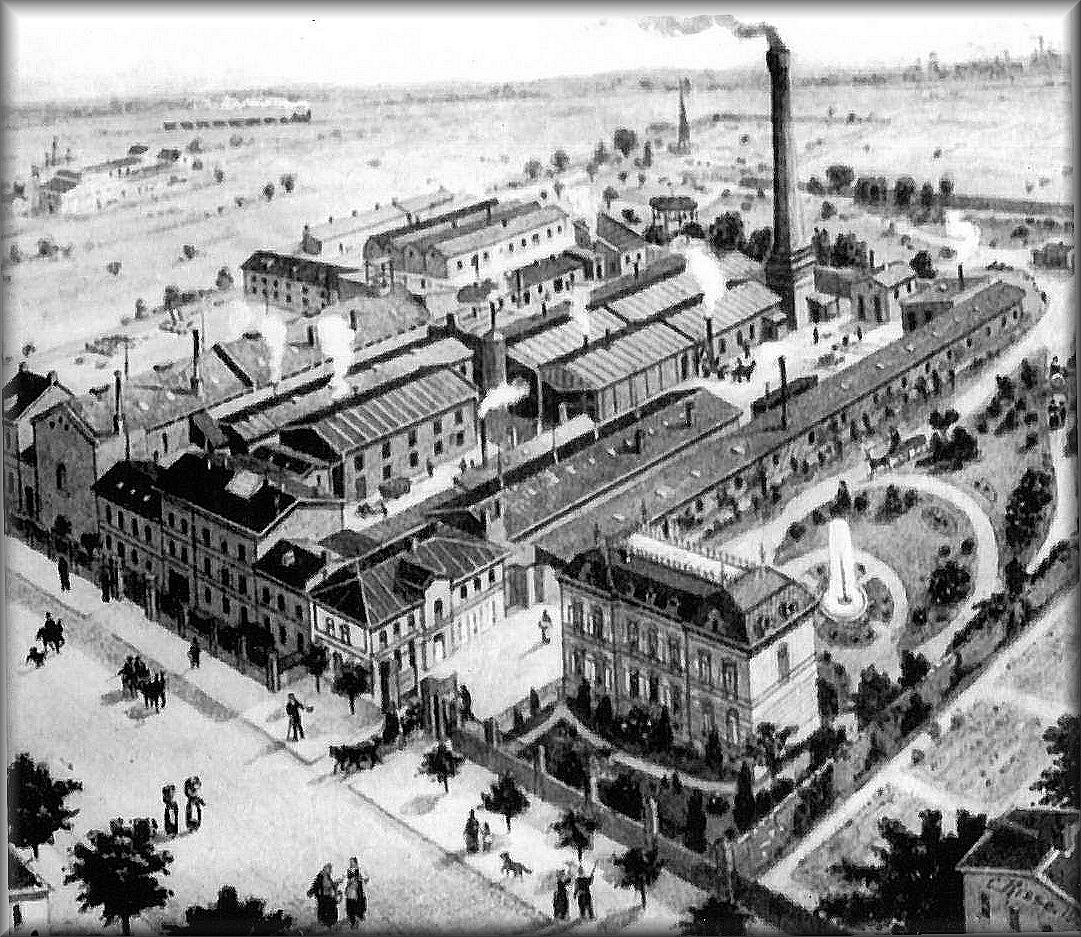

Clouth Factory Front

Younger Franz Clouth

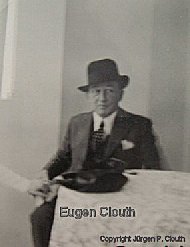

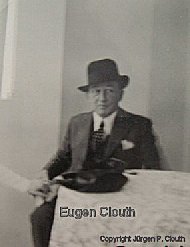

Eugen Clouth

Clouth Factory

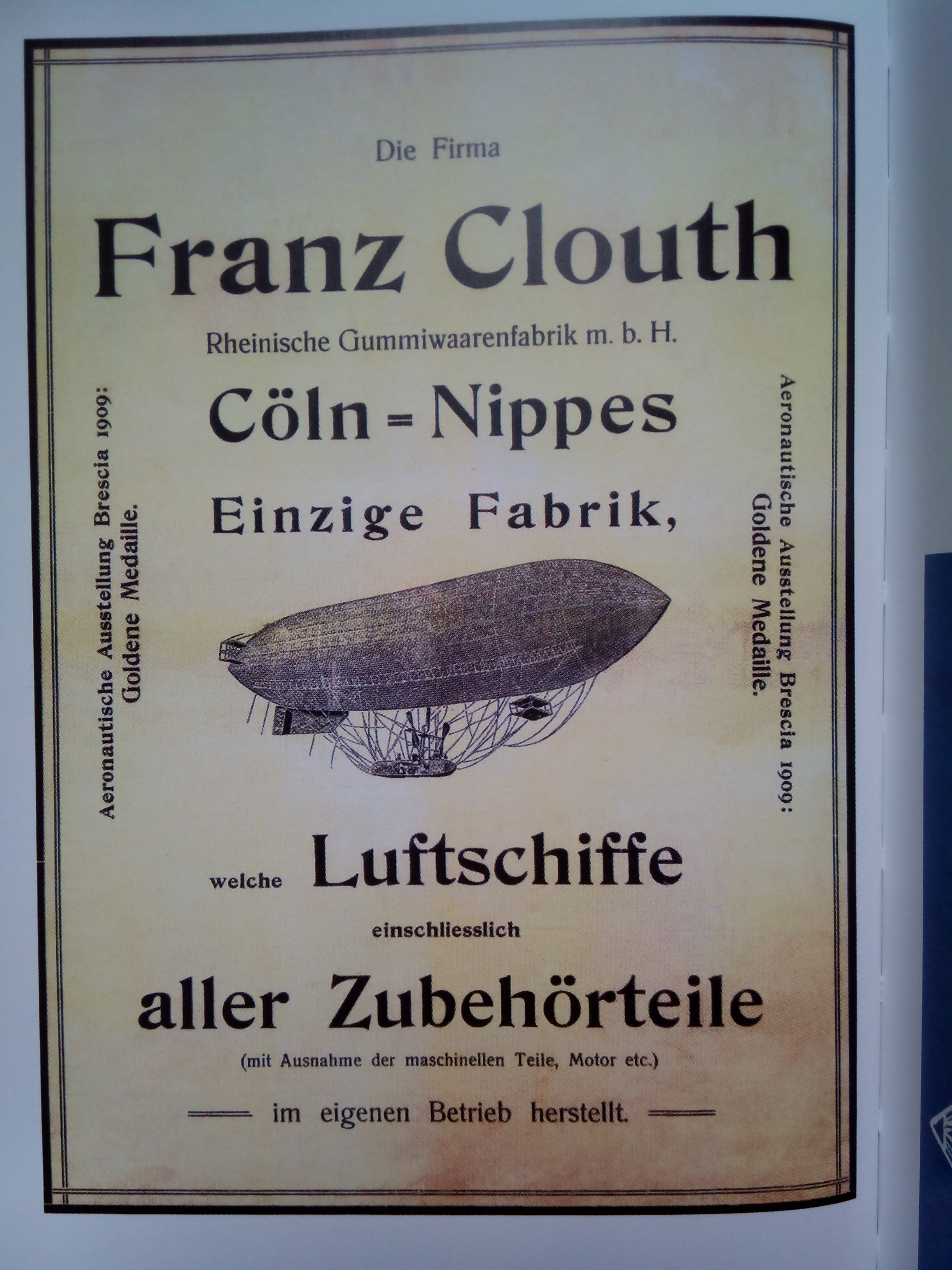

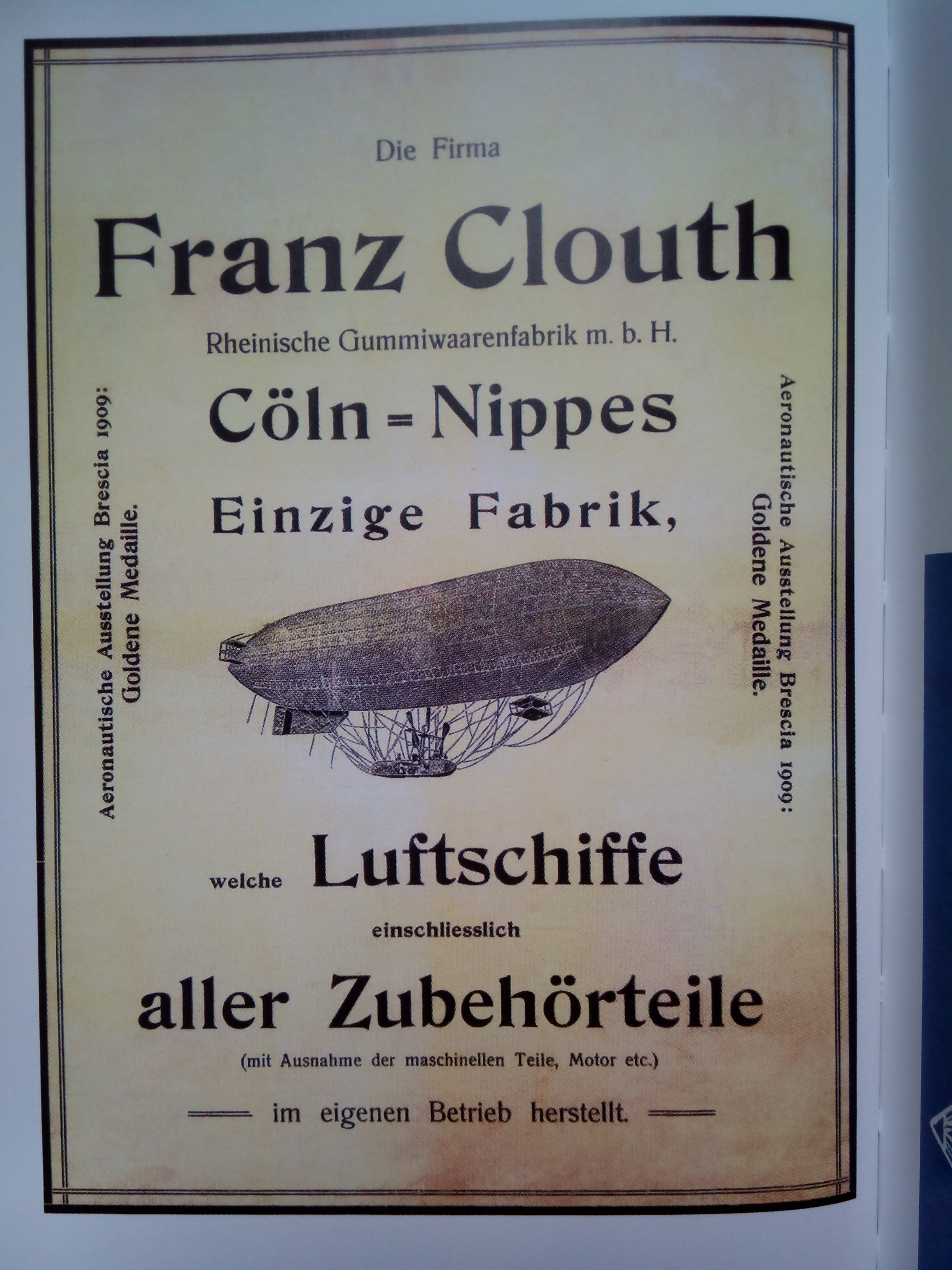

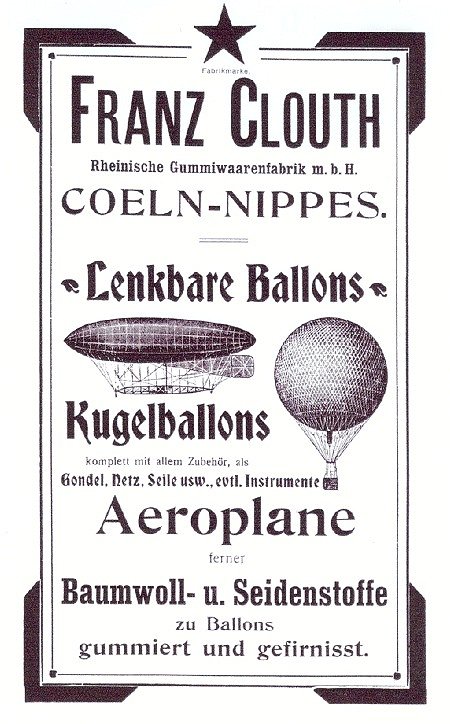

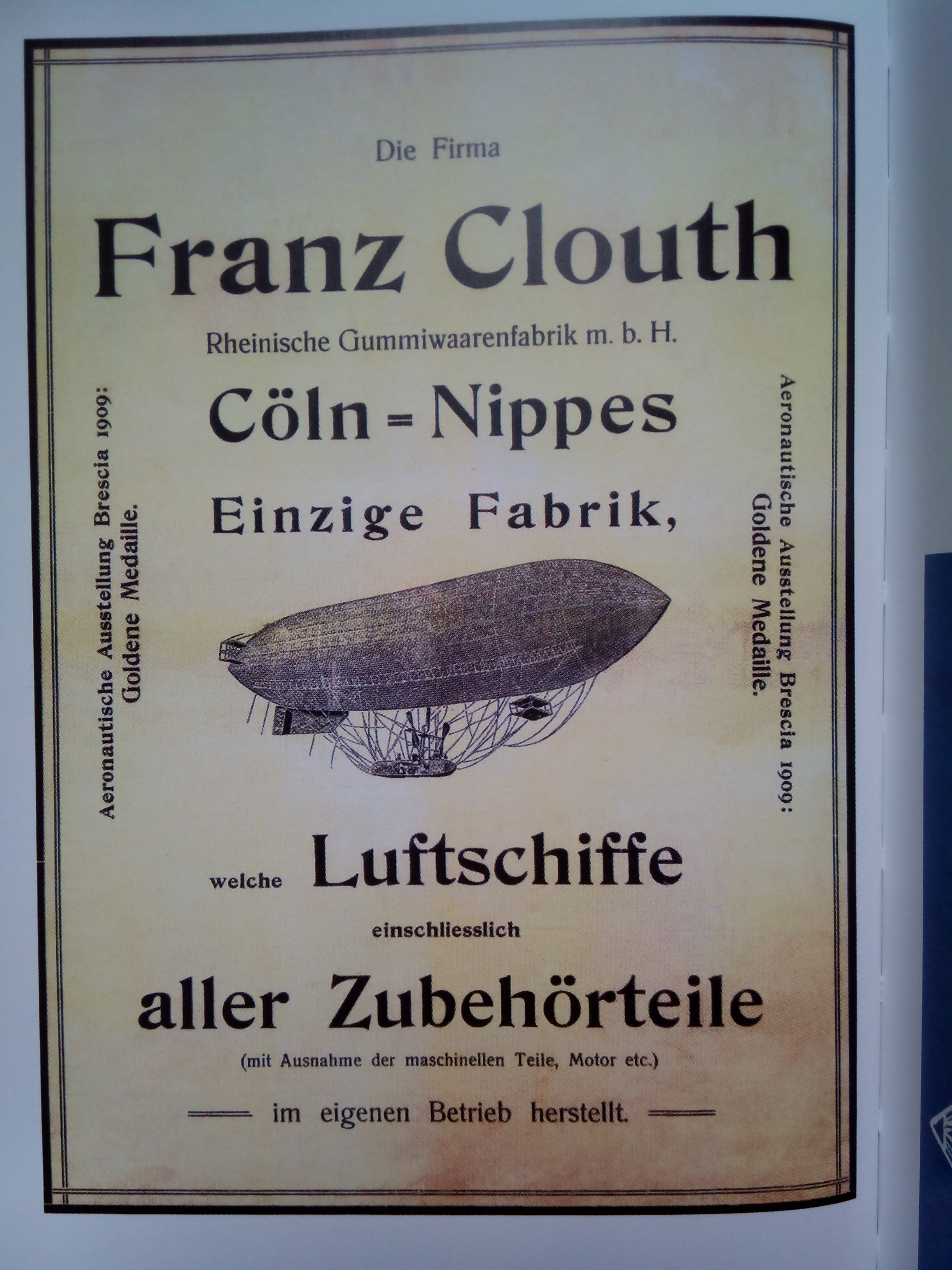

Air Ship Advert

Clouth Money

Old Clouth Crest

Car tyres

Old Car

OLd Daimler

Excavator with conveyor

belt

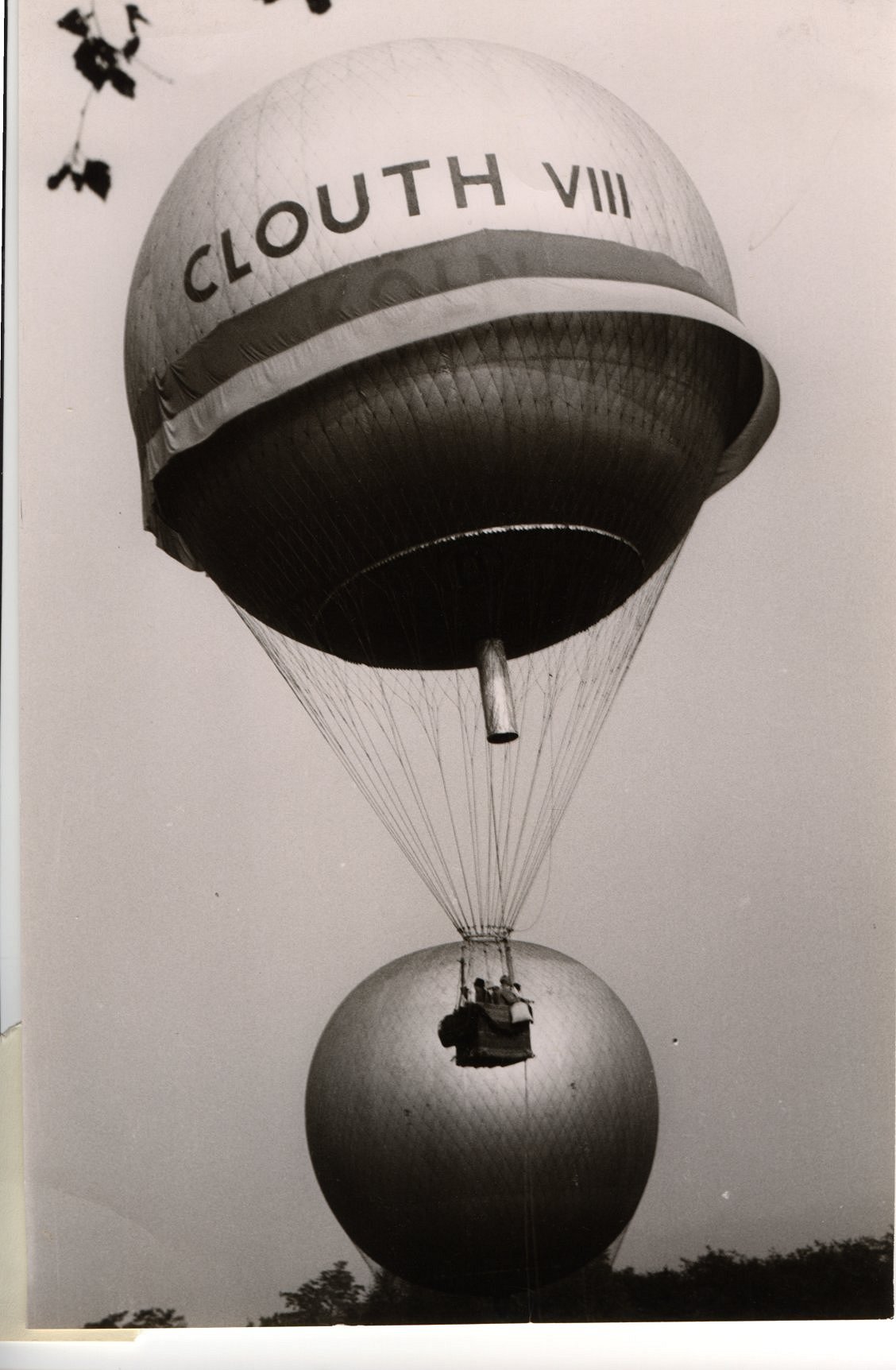

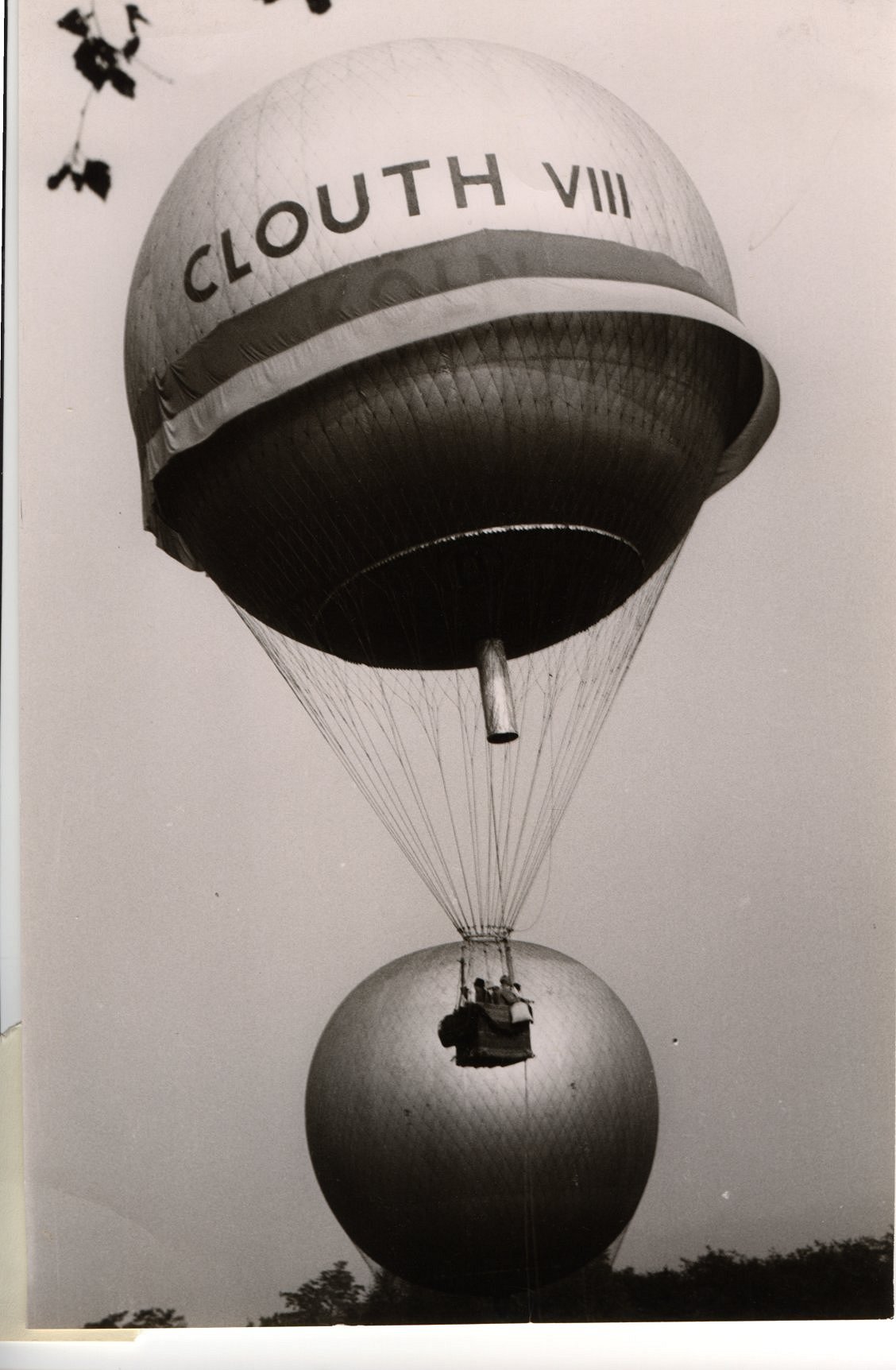

Clouth VIII Balloon

Wilhelm Clouth

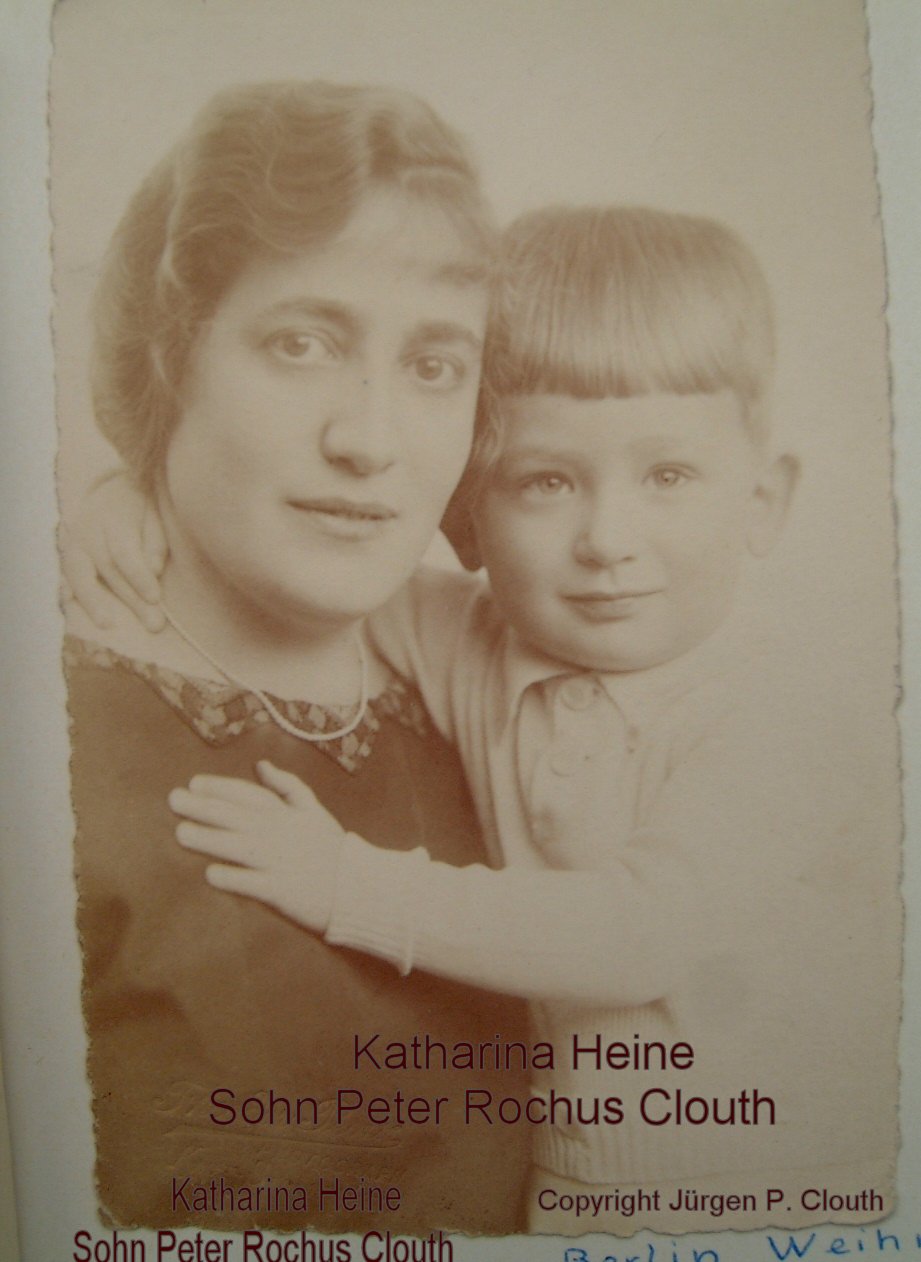

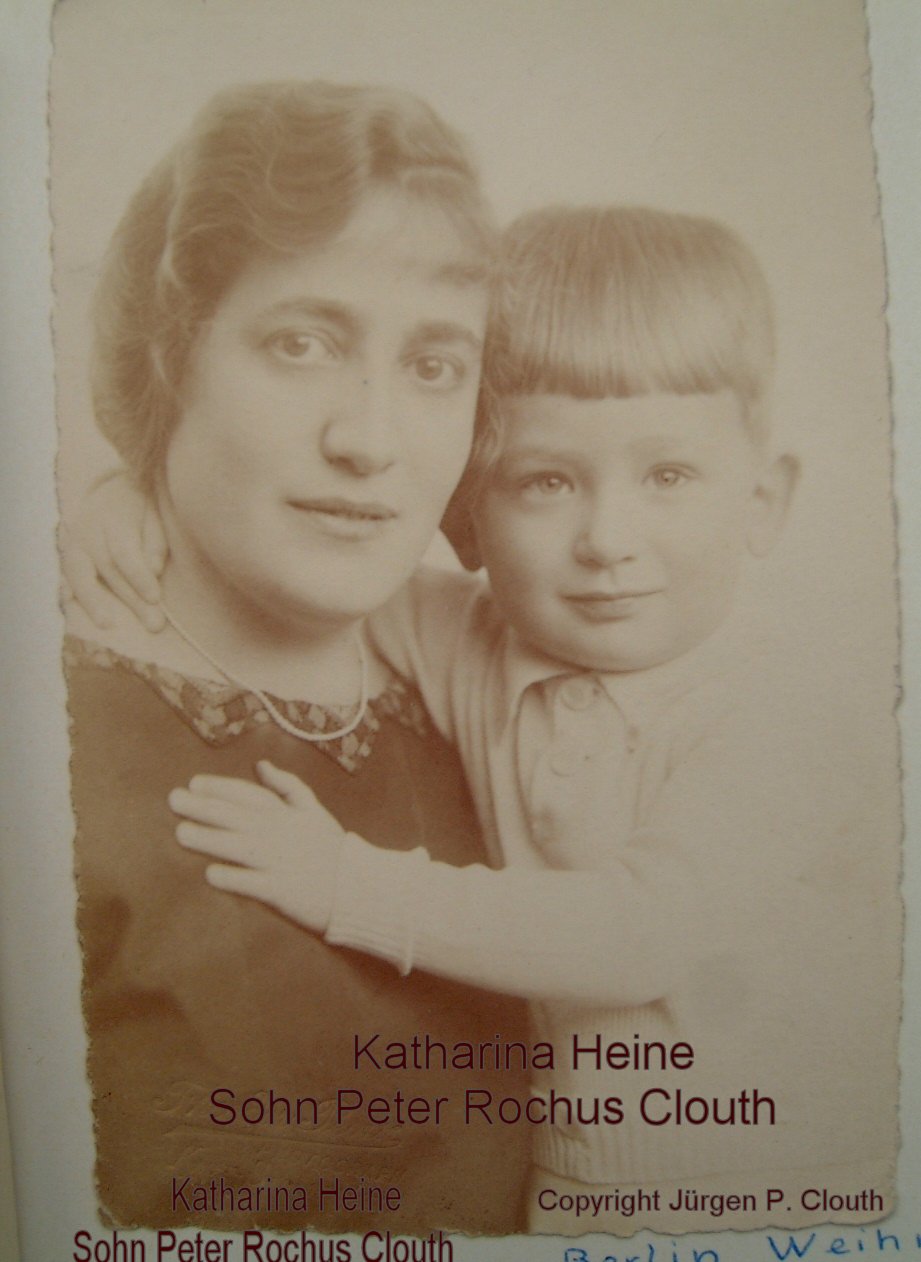

Katharina Clouth

Caoutchouc Golfball

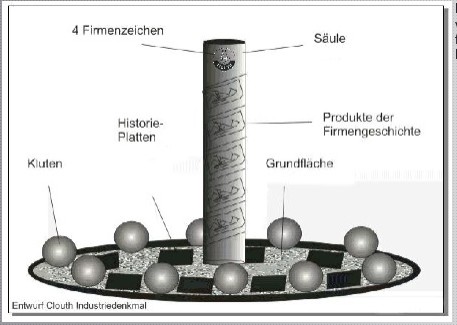

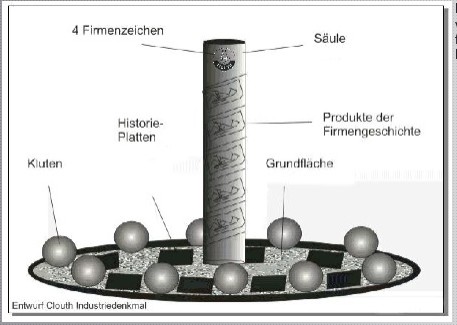

Draft of Clouth Memorial

Old Catholic Church Köln

Cable Tower

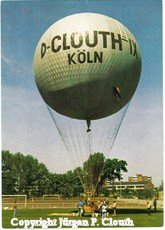

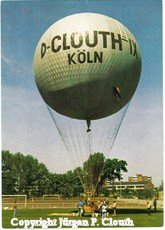

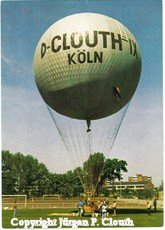

Clouth IX

Ticket for Clouth IX

Drive

Clouth IX

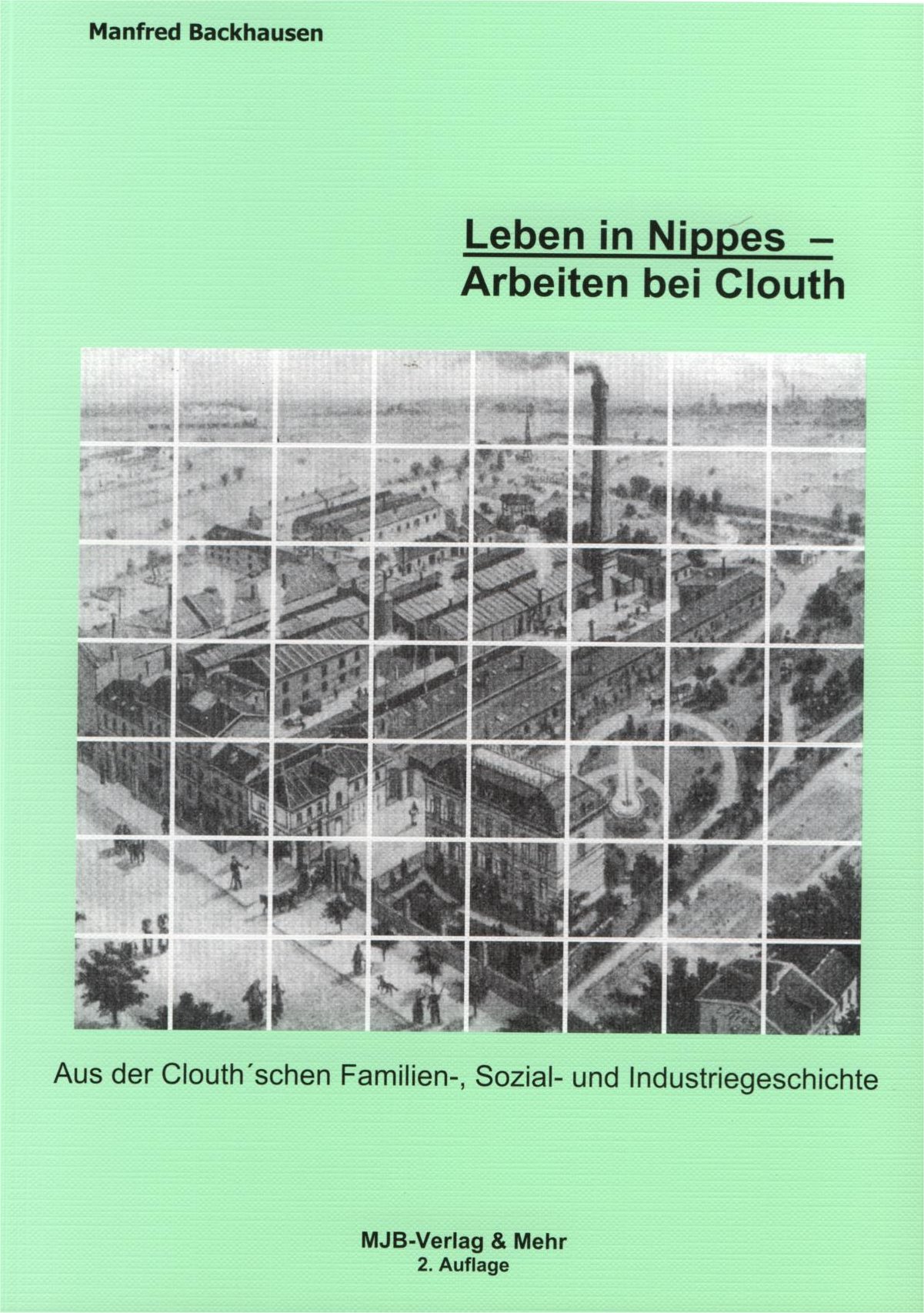

Clouth Buch 2.Edition

.jpg)

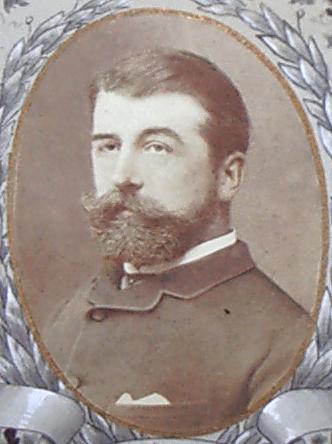

old Franz Clouth

Balloon Gondola

Butzweilerhof Airport

Caoutchouc-Tree

Caoutchouc Sheets

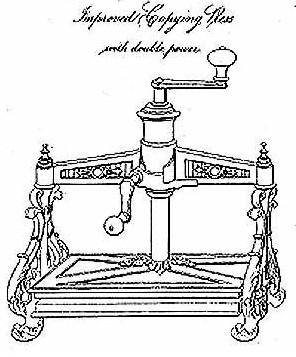

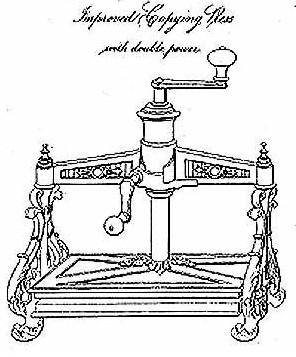

Caoutchouc-Copy Mashine

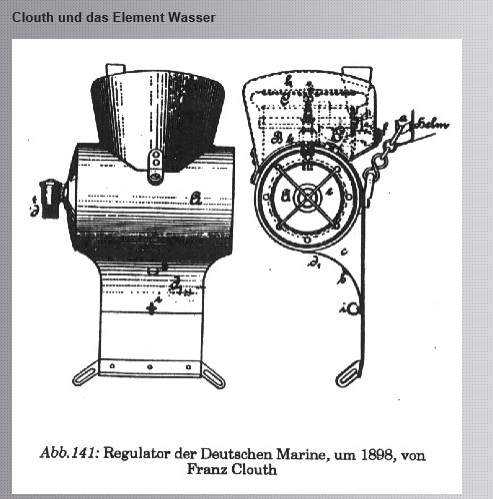

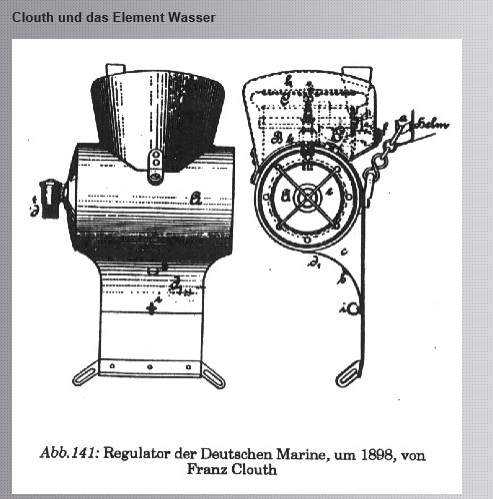

Water-Regulator

old Land & See Logo

Land & See New logo

Franz Clouth

Richard Clouth

Industrieverein Altlogo

Conveyor Belt Hall

Gate 2 to Clouth Works

Atlantic Cable

von Podbielski Cable

Layer

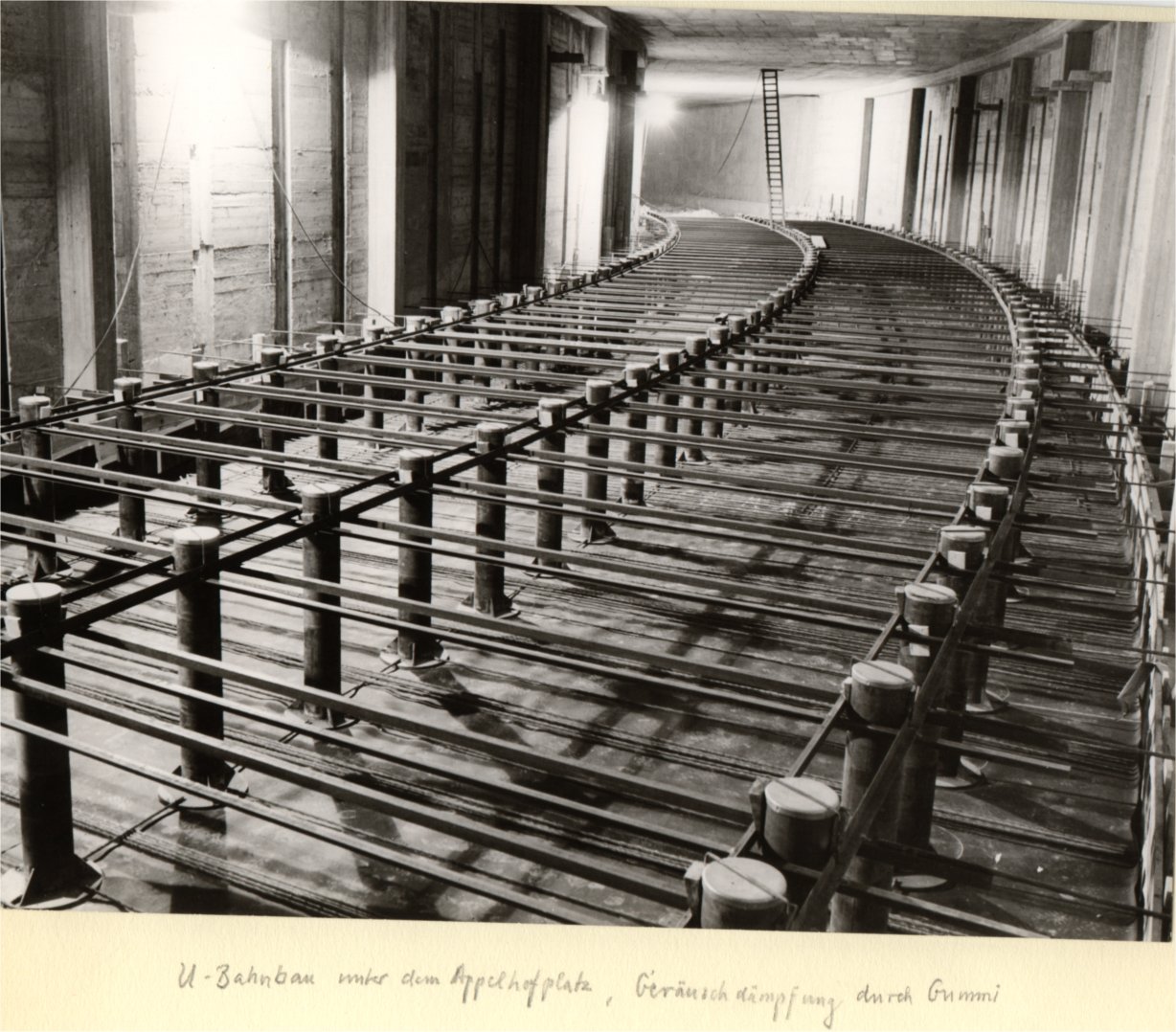

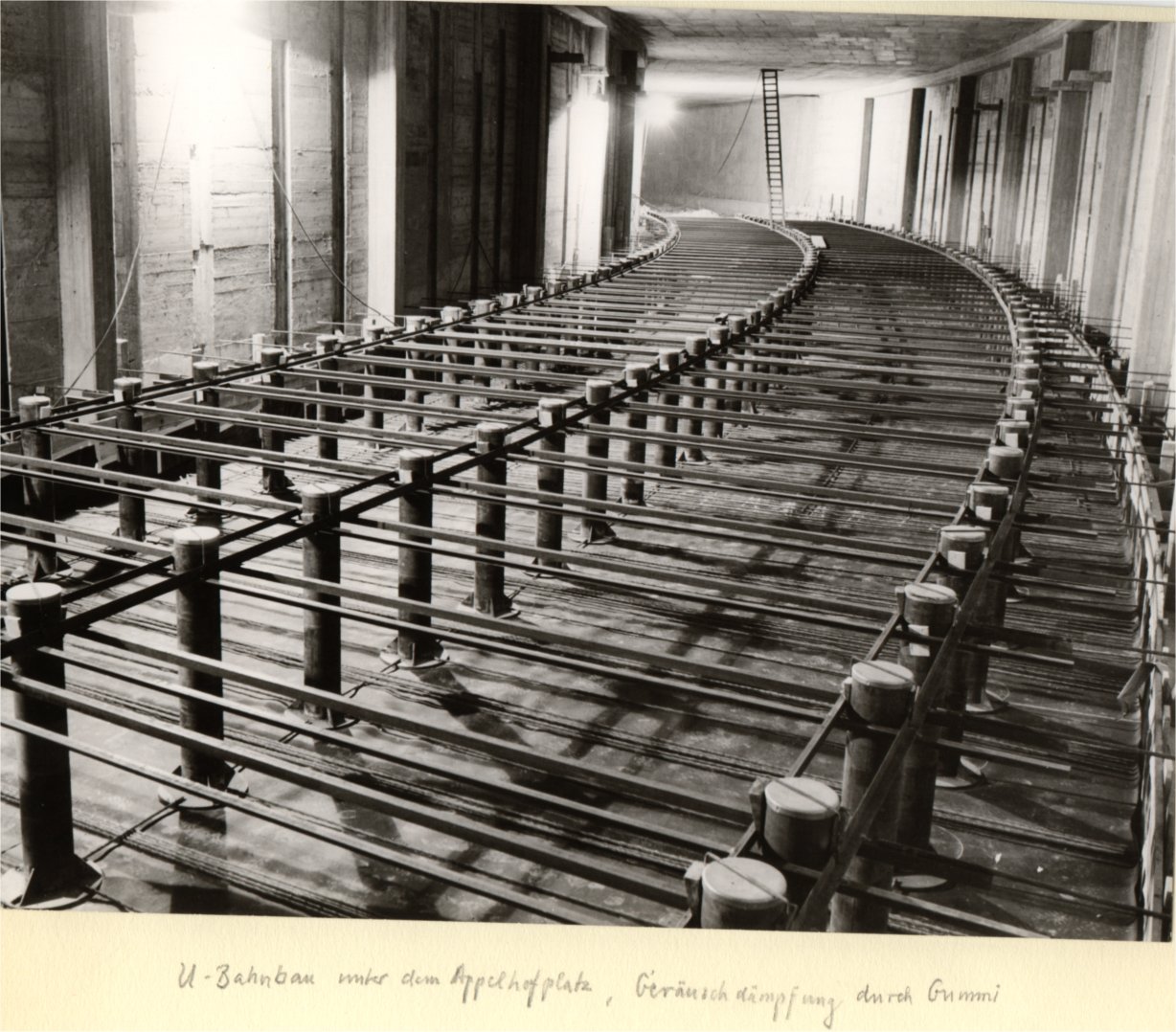

Sound Silencer "Clouth

Ei"(Egg)

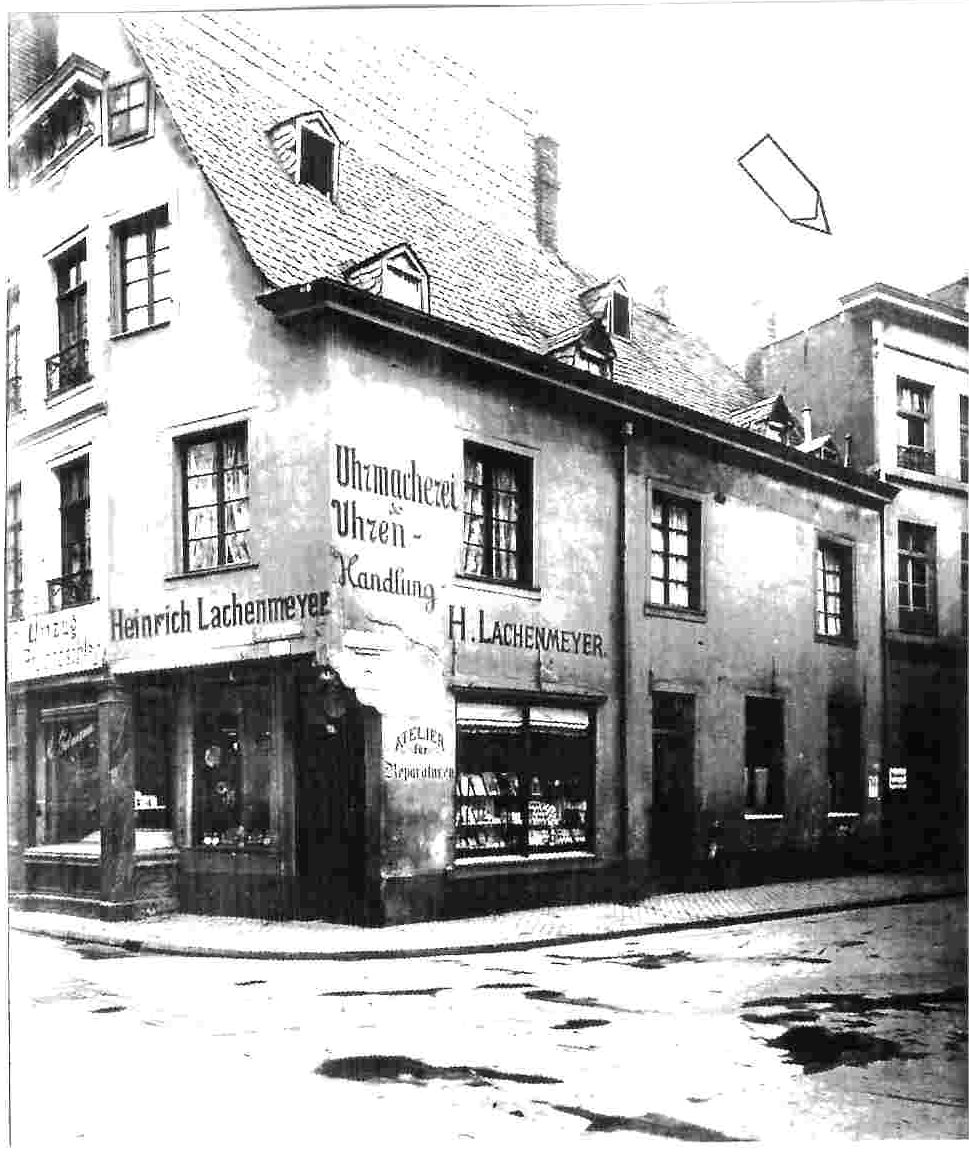

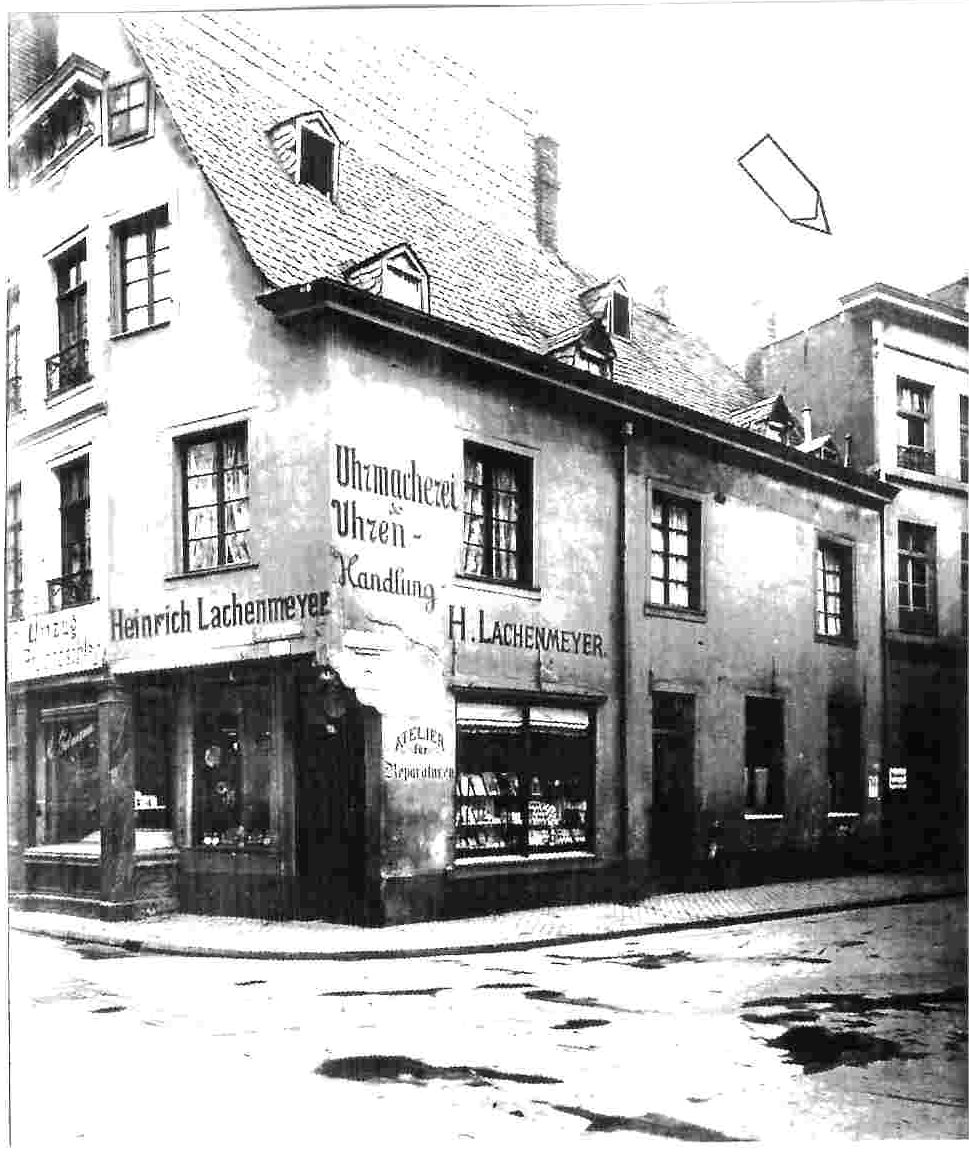

Printery Wilhelm Clouth

| |

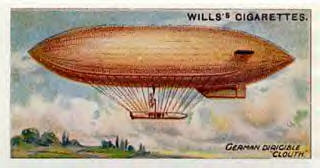

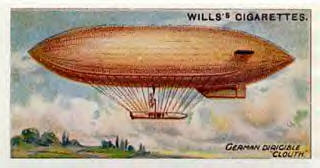

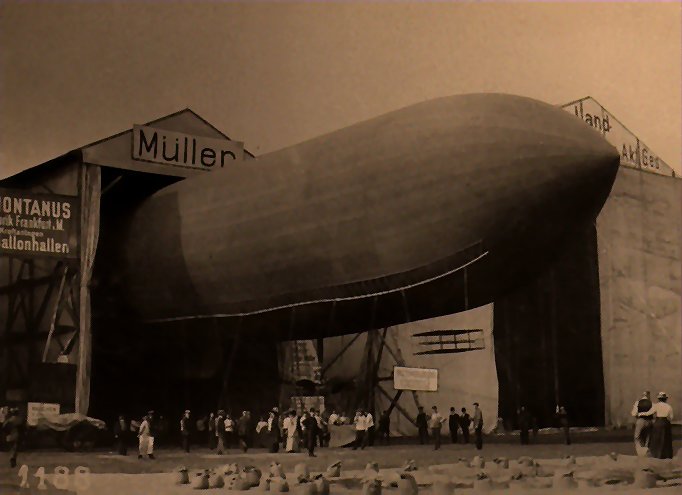

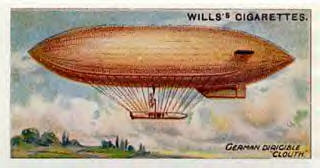

airship aviation

dirigible/airship Clouth

Beginnings

of the aviation exhibition

-

History

-

History in general

-

The air travel history of Cologne and the

region, part 1

-

Reference:

Krause, Thorsten: The aeronautical history of Cologne and the region, part

1. The beginnings of ballooning and airship in Cologne until 1912. With an

escort by Dr. Edgar Meyer, president of the foundation Butzweiler Hof

Cologne. In: Pulheimer Contributions to History and Home Based Learning

2002, vol. 26, pp. 199-231.

-

From the rigid airship "Z1" Graf Zeppelins

to the dirigible airship "CLOUTH"

-

Connections to Graf Zeppelin

-

Emperor's emblem of the Emperor's coat of

arms; No noble predicate like "von" Clouth

-

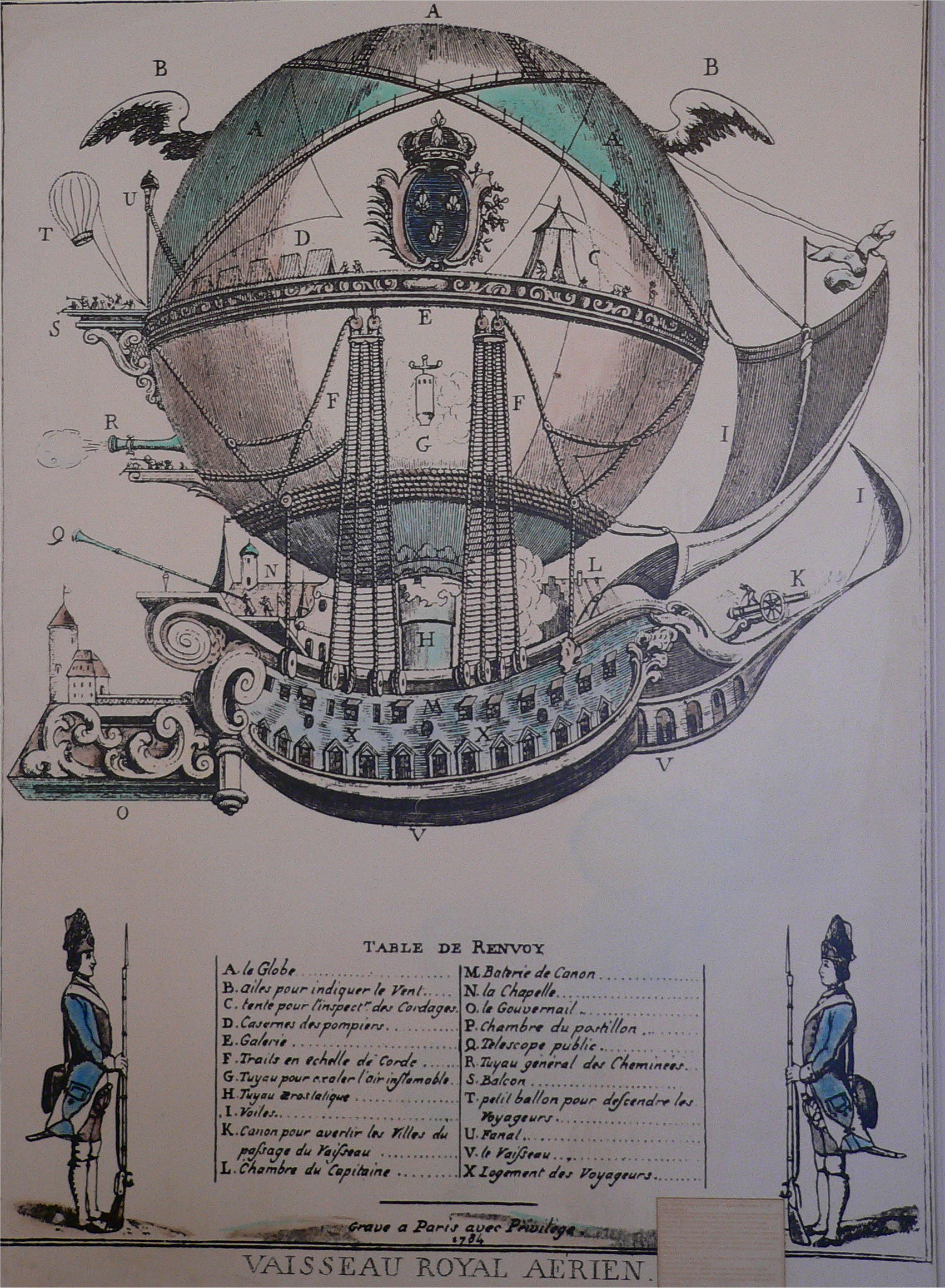

Airship and balloon

history

Airship travel 1909

-

-

From rigid airships like Z1

to dirigibles like "CLOUTH Airship"

-

-

-

Deutsches Luftschifffahrt-Museum

Deutsches Luftschifffahrt-Museum

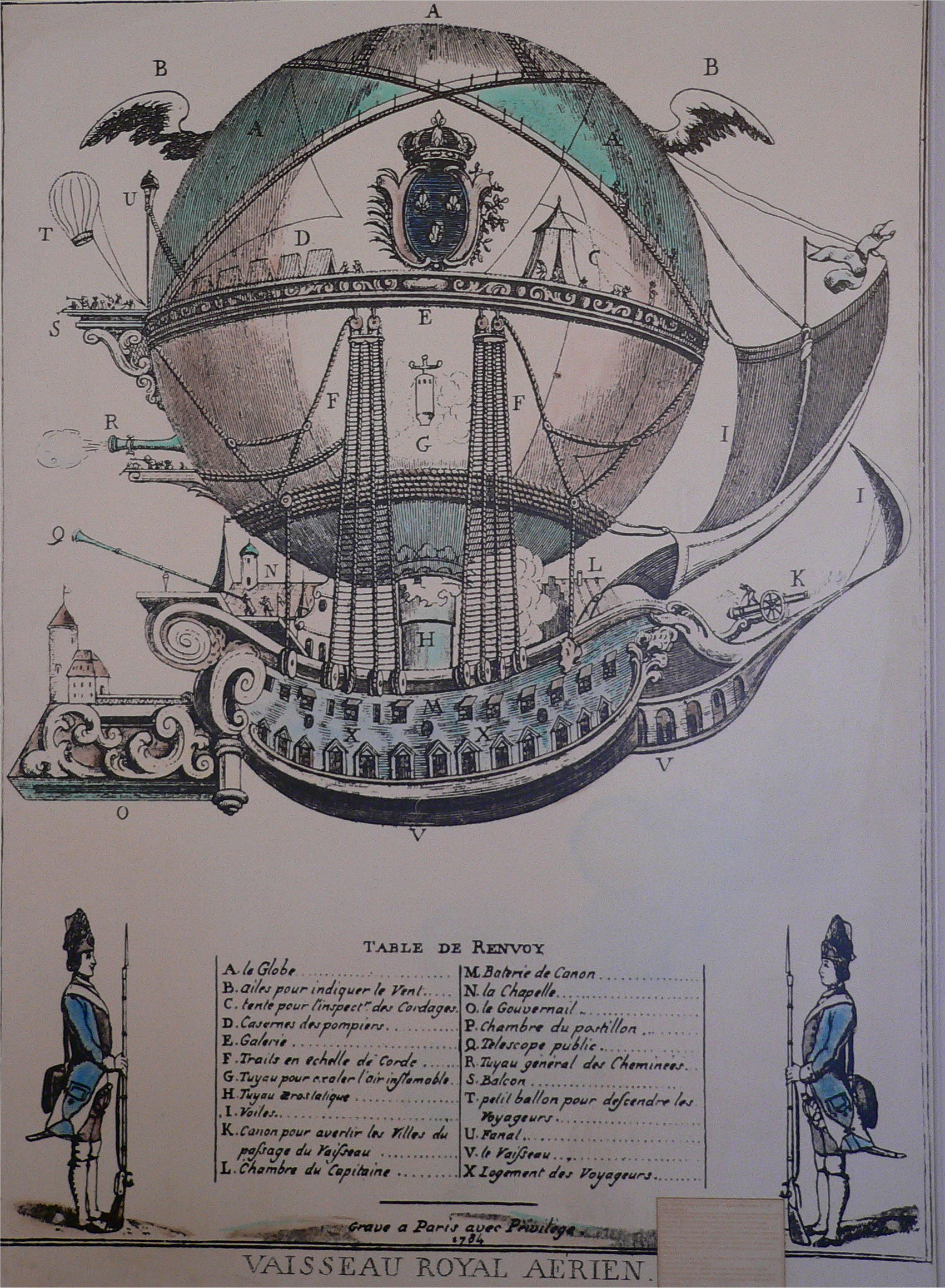

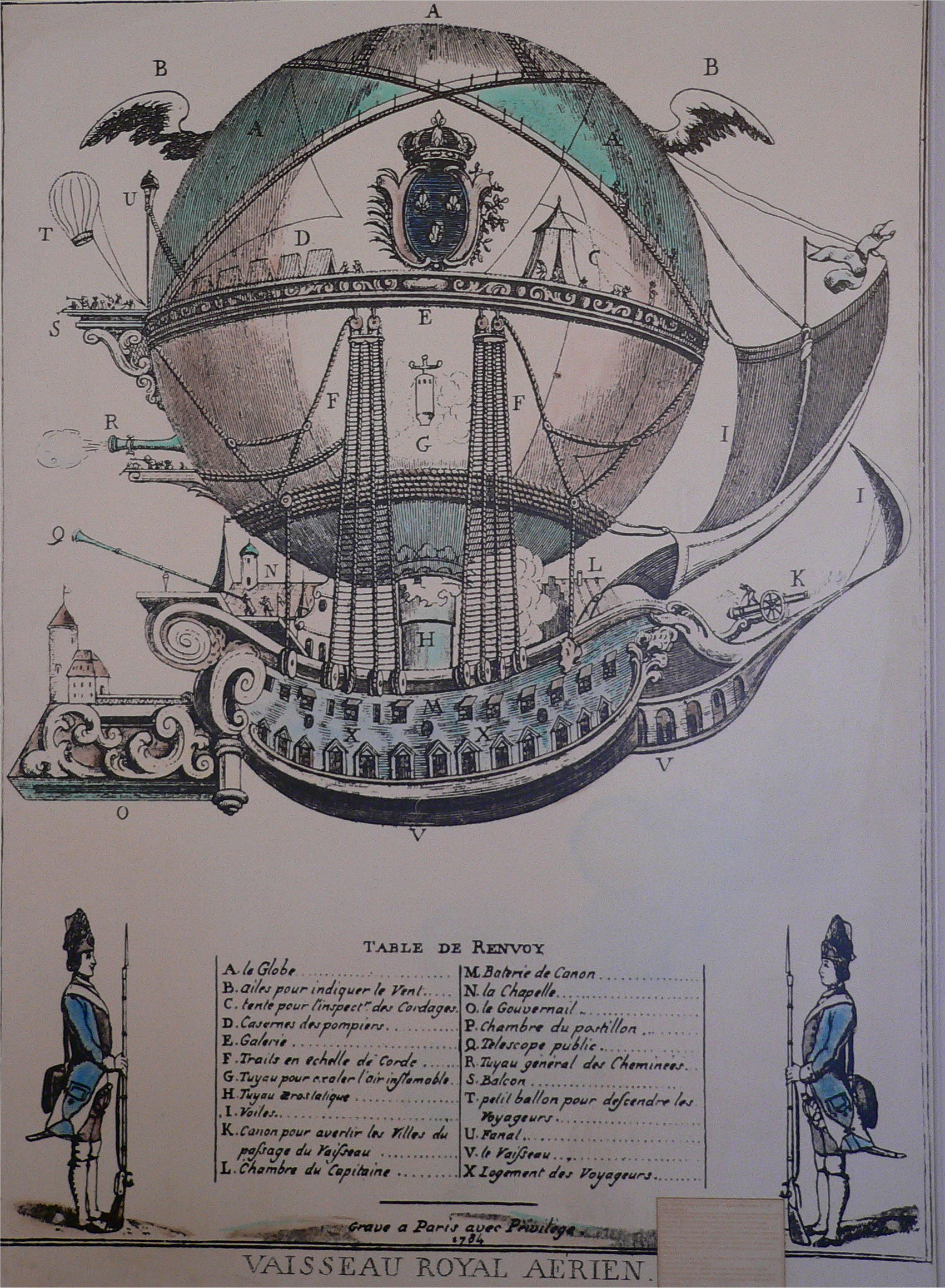

The first ascent of a manned balloon in Germany took place on 3 October 1785 in

Frankfurt am Main. [3]

The Frenchman, Jean-Pierre Blanchard, introduces a series of ballooning

demonstrations on German soil, making the balloon travel widely known in the

German Reich. [4]

In the following the history of the beginnings of the balloon and airship in

Cologne until 1912 is sketched.

Starting from the end of the 18th

century.

This chronological demolition closes with the founding of the military air

station "Butzweilerhof" in 1912.

The focus of the description is on the aircrafts "Lighter than Air" and the

related events within the cathedral city.

Especially

the "Freiballon" (no scaffolding errection) is up to the beginning of the 20.

century the only

aircraft of importance;

Airships or airplanes - later dominant - have not yet been fully developed, as

there is still a lack of suitable propulsion for these aircrafts.

The beginning of the "Motorfliegerei" (engined objects) in Cologne with the

aircraft "heavier than air" is largely excluded in the context of this

consideration.

That chapter in Cologne's history of aviation requires a separate presentation,

as it is just as complex as event-driven and flight pioneers, like this one,

which is to be described here. In the following the history of the beginnings of the balloon and airship in

Cologne until 1912 is sketched.

Starting from the end of the 18th

century.

This chronological demolition closes with the founding of the military air

station "Butzweilerhof" in 1912.

The focus of the description is on the aircrafts "Lighter than Air" and the

related events within the cathedral city.

Especially

the "Freiballon" (no scaffolding errection) is up to the beginning of the 20.

century the only

aircraft of importance;

Airships or airplanes - later dominant - have not yet been fully developed, as

there is still a lack of suitable propulsion for these aircrafts.

The beginning of the "Motorfliegerei" (engined objects) in Cologne with the

aircraft "heavier than air" is largely excluded in the context of this

consideration.

That chapter in Cologne's history of aviation requires a separate presentation,

as it is just as complex as event-driven and flight pioneers, like this one,

which is to be described here.

This presentation is mainly based on the documents and records compiled and

archived by the Butzweilerhof Foundation in Cologne [5]

In addition, general literature on the history of aviation as well as

corresponding documents from archives are used to round out the picture.

II. Civil and military balloon and airship

II. 1 Civilian balloon and airship

The first attempt to conquer Cologne in Cologne, which however remained

unsuccessful, is handed down for the year 1785.

When Jean-Pierre Blanchard arrives in Cologne on October 21, 1785, on his round

trip through the German Empire, the latter sends a request to the city to be

allowed to rise in the Rhine metropolis with his balloon.

The Cologne City Council rejected Blanchard's request: the city fathers argue

that it is presumptuous against God's mercy to do such things. [6]

The city of Cologne issues a start ban and allows the trained mechanic and

engineer only a public presentation of his balloon.

With the approval of the balloon ascent two and a half weeks earlier, the City

Council of Frankfurt a. Main was more open-minded than the cathedral city. [7]

The refusal of Cologne's mayor of the Cologne may be due to the fact that the

balloon was regarded as a symbol of enlightenment and technical progress, some

even as a sign of revolution and upheaval.

The predominantly bourgeois conservative population and the cathedral city,

which is concerned with peace and order, probably want to distance itself from

these political dimensions. [8]

Despite this concern on the part of the city, balloon climbs can not be

completely removed from the surrounding countryside of Cologne or the Rhineland.

[9]

In May, June and July, 1788, the Land Physician of the Monheim Office, Georg

Haffner, opened a balloon of his own design in Deutz. [10] Haffner announced his

plan in advance by means of a newspaper. [11]

Only after clearing out some concerns of the archbishop of Cologne and Elector

Maximilian Franz, a Deutzer Amtmann (civil servand) - Deutz was then still a

neighbor city of Cologne [12] - with permission of the Cologne Stadtherren

Haffner's permission for his balloon demonstration. [13]

Further balloon ascents from Haffner, whether without or with human occupation,

seem to have stopped.

According to Haffner's departure from Deutz, there are several letters of

complaint which the aeronauts are alleged to be in breach of payment. [14]

Like the Frenchman Jean-Pierre Blanchard, the "balloonist of the first European

aviation enthusiasm" [15], Georg Haffner is one of the few professional aviators

at the end of the 18th century in

Europe.

He belongs to the group of showman aeronauts, who follow the example of

Blanchard and run the ballooning professionally from genuine enthusiasm.

Often they have to finance the construction of their balloons themselves from

the revenues of their performances.

At this time, only a few people are allowed to ascend.

The balloonists call themselves 'aeronauts' or to German 'Luftschiffer';

As "captains" they "ride" in the "air sea" and dress in marine uniforms. Like the Frenchman Jean-Pierre Blanchard, the "balloonist of the first European

aviation enthusiasm" [15], Georg Haffner is one of the few professional aviators

at the end of the 18th century in

Europe.

He belongs to the group of showman aeronauts, who follow the example of

Blanchard and run the ballooning professionally from genuine enthusiasm.

Often they have to finance the construction of their balloons themselves from

the revenues of their performances.

At this time, only a few people are allowed to ascend.

The balloonists call themselves 'aeronauts' or to German 'Luftschiffer';

As "captains" they "ride" in the "air sea" and dress in marine uniforms.

In the course of the 19th century,

Balloon demonstrations are gaining popularity by famous and less prominent

aeronauts.

In addition to the events in well-known amusement centers in front of an

'upscale' public, the balloon also plays an attractive role in the annual

markets and national festivals.

By enriching the previous flight program, parachute jumps and night trips, the

conditions for an increased and wider publicity of the balloon are created.

Initially it is mainly foreign aviatics who perform balloon demonstrations in

Germany: "Germany did not have balloons in the 19th century either of international reputation. "[16]

Accordingly, numerous climbs are also taking place in Cologne mainly by French

and English aeronauts.

The aeronauts Sinval and Guerin could have organized such demonstrations in

Cologne in April and May of 1808.

In the Cologne newspapers "Gazette Française de Cologne" and "Der Verkündiger",

they are often advertised. [17]

In this, they announce their intention to get a balloon, from which Monsieur

Guerin will then jump with a parachute.

At the beginning of May, 1847, the Englishman Charles Green [18] gave a guest

performance in the cathedral, where he carried out two ballooning competitions.

[19]

During his stay, Green presents his balloon with an improved parachute for

sightseeing.

Green is one of the most famous and successful aeronauts of the 19th century.

In his self-designed 'Royal Vauxhall balloon' he succeeded on 7th /

November 1836 a spectacular journey from London to the Duchy of Nassau.

In March, 1878, Gustave Landreau, an aviatist from Brussels, asked the Cologne

police chairman to be allowed to rise in the city together with his colleague,

Palont, on May 15 and 19, 1878. [20]

A remarkable personality of the Cologne balloon history of the late 19th century

is Maximilian Wolff.

The learned bookbinder master is one of the founding members of the "German

Association for the Promotion of Air Navigation", founded in Berlin on September

8, 1881, the oldest organization of aviation-inspired people. [21]

In 1889 Wolff was again found in Cologne as an engineer and executive director

of the "Ballon-Sport-Club Cöln, founded 1888".

In 1890, he founded the "Verein zur Förderung der Luftschiffahrt, Cöln" as a

counterpart to the Berlin predecessor and became the chief editor of the

collection "Das Luftschiff" [22].

Since the 1880s, the Aeronaut has been running a permanent attraction in the

Riehler "Golden Corner" (Goldenes Eck) [23] by balloon flights with passengers,

which make it well known across the borders of Cologne.

Thus, Wolff uses his practical knowledge

in the field of air shipping to earn money.

Spectacular is the performance in the late evening of June 10, 1889, during the

"General Exhibition for Household Supplies and Food" in the Riehler "Golden

Corner". [24]

On an approximately 50 m long rope his balloon 'Hohenzollern' draws a

"compilation of different fireworks bodies", according to the report of a

Cologne newspaper [25].

At some altitude Wolff ignites numerous colorful light-bulbs that illuminate

the sky above Cologne.

Two days earlier, Wolff had a misfortune in the course of the "International

Sports Exhibition" [26] taking place there at the same time: his balloon

'Colonia' burst during filling, the smaller one was launched in a hurry with the

name 'Schwalbe'.

About a year later, on July 7, 1890, Wolff once again passed a mishap, this time

with more serious consequences: On a trip from Cologne to Bensberg, his balloon

'Stollwerck' is captured during the landing by a sudden wind breeze.

This ripped one of the eight agricultural workers who helped with the landing,

the passenger Peter Schmitz, who is still in the basket, among other things,

President of the Blue Spark, as well as Wolff himself.

Shortly afterwards, the farmhand crashes and is seriously injured, Peter Schmitz

and Wolff can later leave the balloon uninjured.

Following these events, the authorities are accused of neglecting the lives of

their passengers. [28]

Obviously, the spread of this type of balloon accident, which is the subject of

numerous articles of the time, [29] sensitizes the population.

The authorities are increasingly demanding that similar investigations should be

avoided in the future.

On May 19, 1894, the Cologne police chief received a letter in which he was

warned not to grant permission to a balloon lift in Cologne to the aeronaut

Robert Feller, Ferrel. [30]

According to the author of the letter, Feller is jeopardizing his passengers

because of his drinking habits.

What specific measures are being taken is not known;

A year later, Ferrel is again to be found in his professional career in the

Riehler "Golden Corner". [31]

Here, "Captain" Ferrel appears together with the well-known air bailiff "Miss

Polly".

"Miss Polly", which is called Luise Giese née Schleifer, belongs to the few

(besides the well-known Frankfurt parachute artist and balloonist

Käthe Paulus) women in

this trade. [32]

Since both women appear in matry costumes and bear the artist name "Miss (with

two 's') Polly" or "Miss (with 'ß') Polly" and are thus only to be distinguished

by their different notation, they are frequently confused.

Both aeronauts are in the Rhineland, and they are also offered engagements in

numerous cities abroad.

The

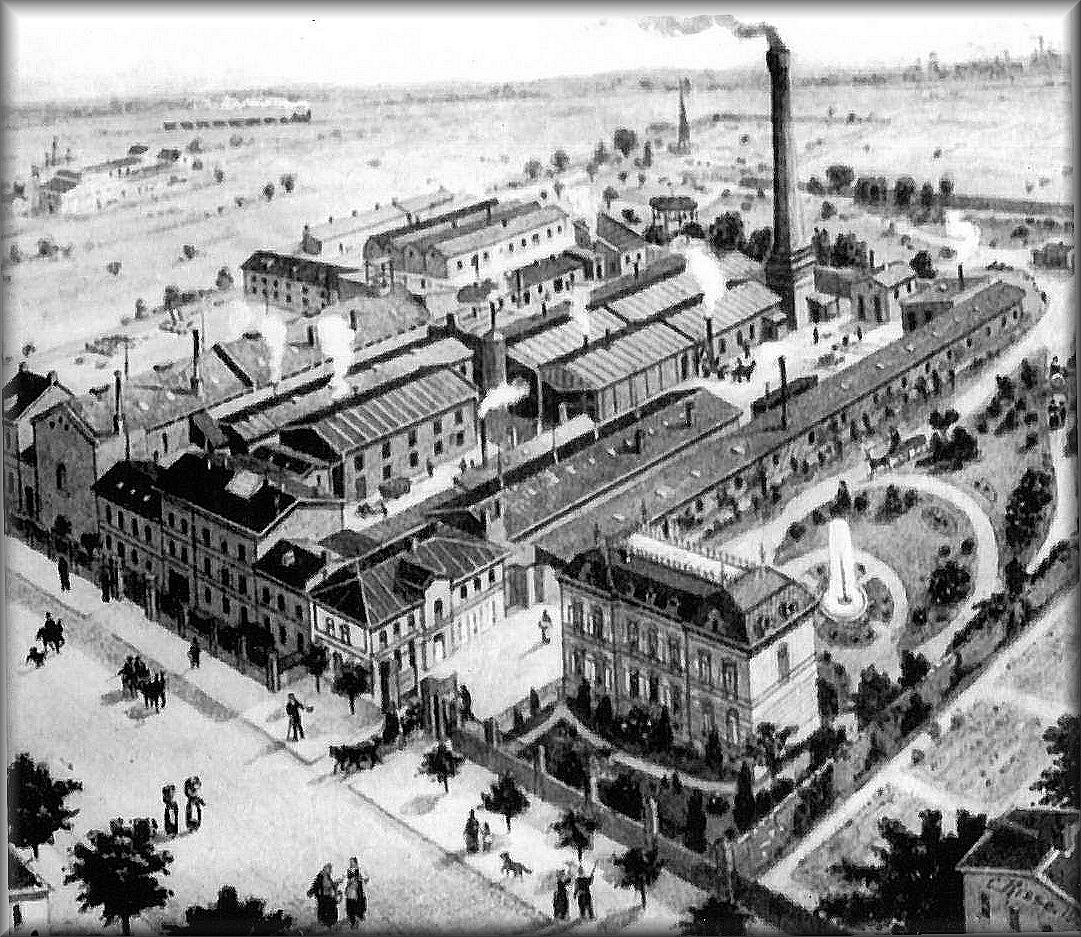

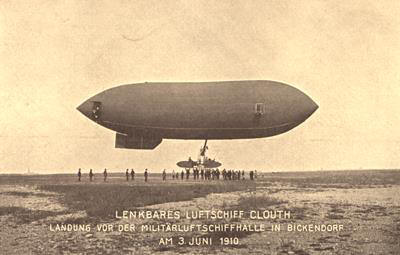

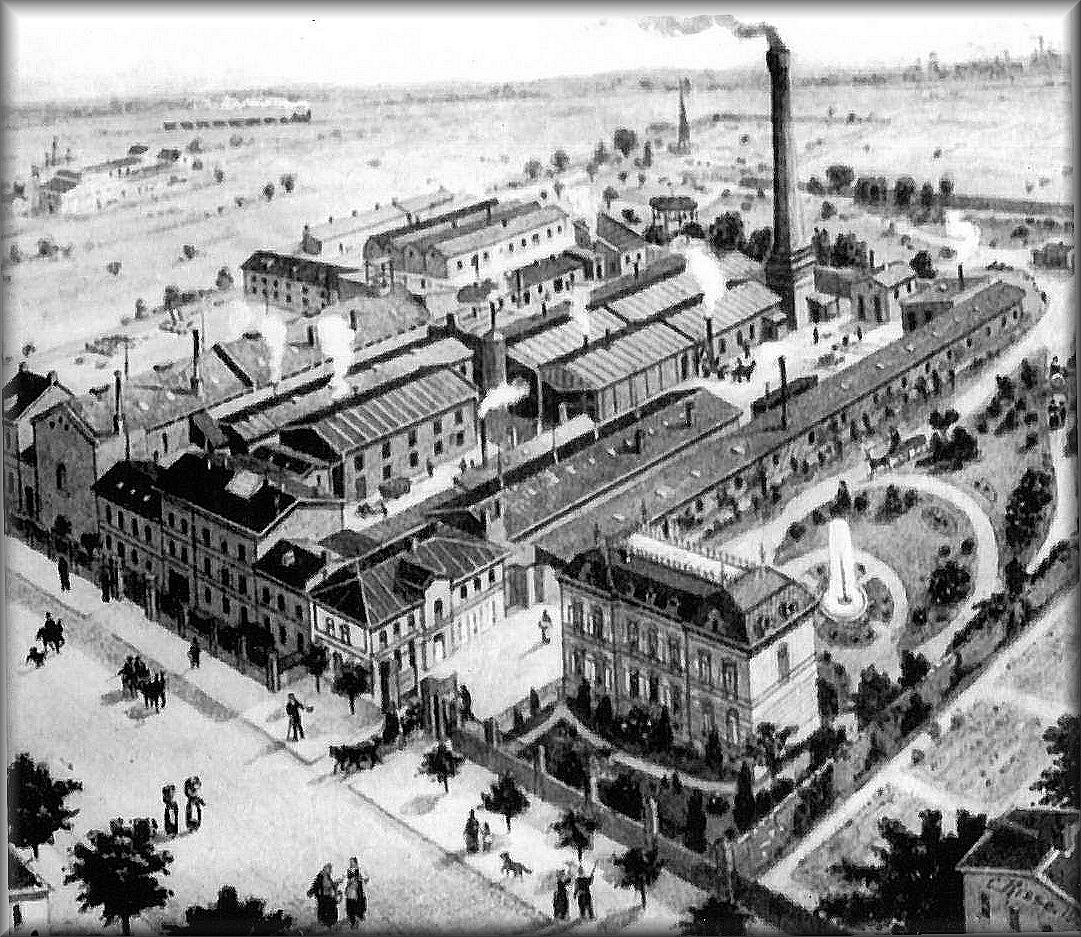

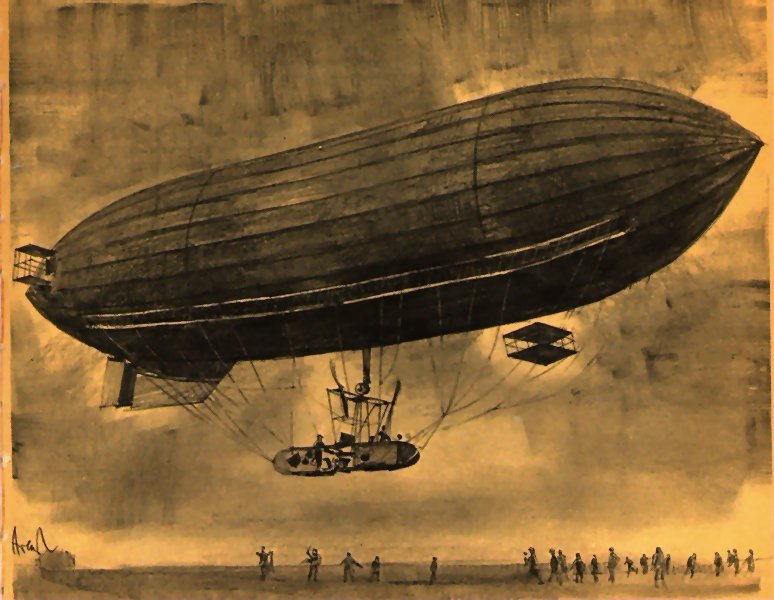

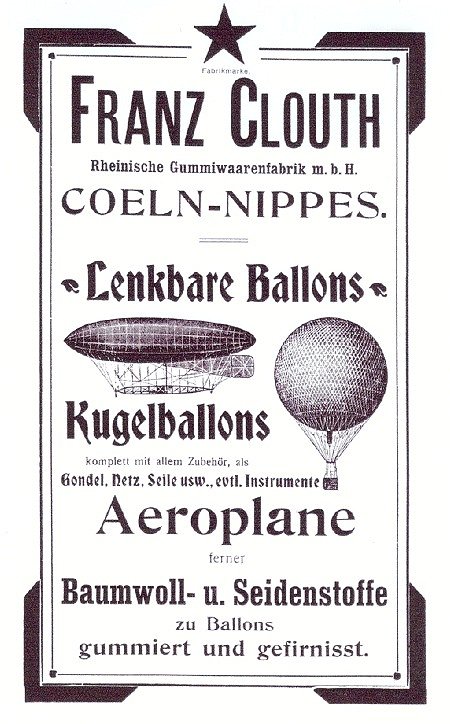

Cologne-based manufacturer Franz Clouth made an important contribution to both

the Cologne and the general development of aviation as well as the urban

industrialization process with his company "Franz Clouth Rheinische

Gummiwarenfabrik Cöln-Nippes".

At the end of the 19th century, the company, which was founded in 1862 and has

been producing rubber products of all kinds, is dedicated to the manufacture of

balloon materials and complete balloons, as well as the development and

construction of a

dirigible like "CLOUTH

Airship.

[36]

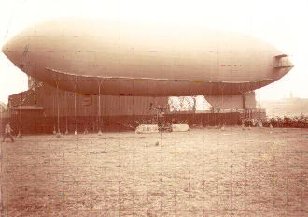

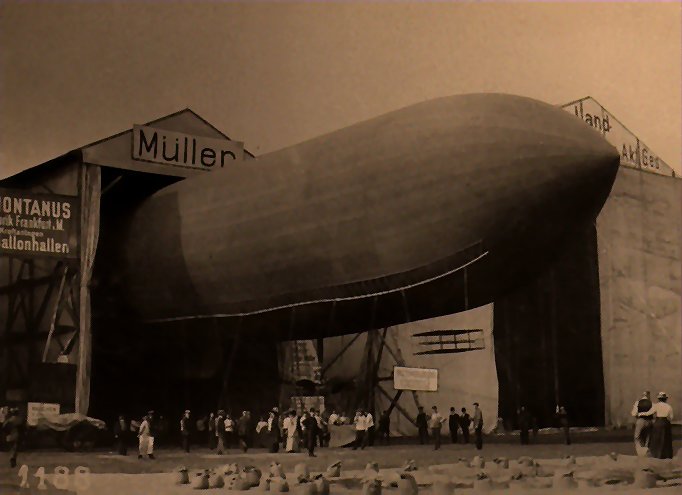

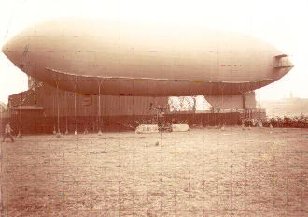

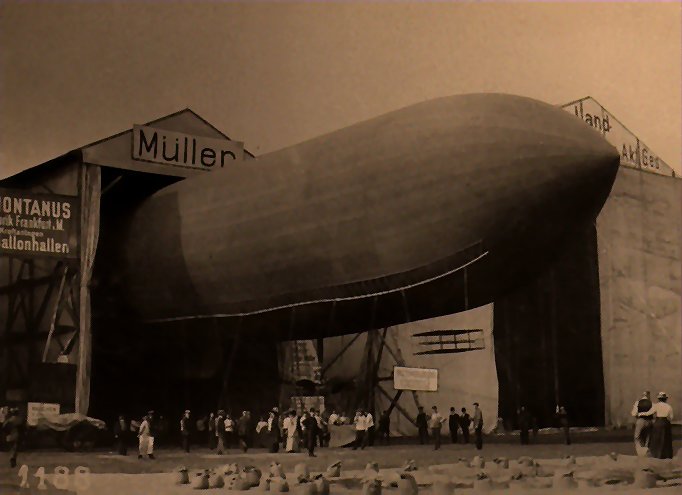

As early as 1908, the airship 'Clouth I' undertook his maiden voyage over Nippes.

For the development and construction of the airship about one and a half years

were required, all parts except the engine were custom made of the company

Clouth.

For the construction of 'Clouth I', 1907 the probably first architectural

testimony of a - in the broadest sense - air transport architecture in Cologne:

a 45 m long, 29 m wide and 17 m high airship hall was erected on the factory

premises in Cologne-Nippes

Corporate balloons and the airship later served as a "home port." [37]

In 1909 the The

Cologne-based manufacturer Franz Clouth made an important contribution to both

the Cologne and the general development of aviation as well as the urban

industrialization process with his company "Franz Clouth Rheinische

Gummiwarenfabrik Cöln-Nippes".

At the end of the 19th century, the company, which was founded in 1862 and has

been producing rubber products of all kinds, is dedicated to the manufacture of

balloon materials and complete balloons, as well as the development and

construction of a

dirigible like "CLOUTH

Airship.

[36]

As early as 1908, the airship 'Clouth I' undertook his maiden voyage over Nippes.

For the development and construction of the airship about one and a half years

were required, all parts except the engine were custom made of the company

Clouth.

For the construction of 'Clouth I', 1907 the probably first architectural

testimony of a - in the broadest sense - air transport architecture in Cologne:

a 45 m long, 29 m wide and 17 m high airship hall was erected on the factory

premises in Cologne-Nippes

Corporate balloons and the airship later served as a "home port." [37]

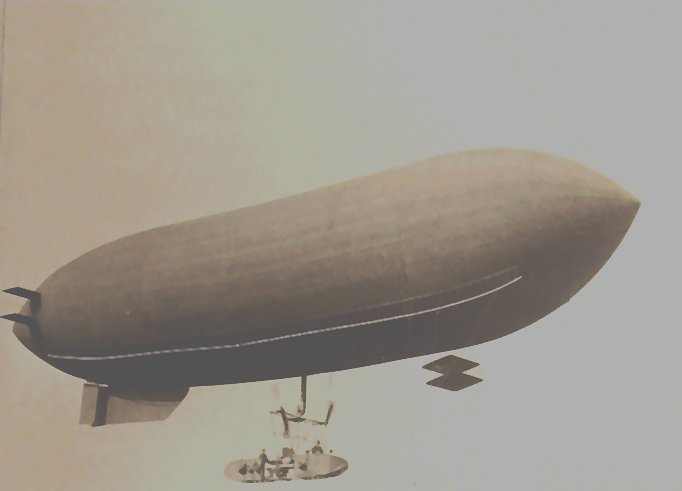

In 1909 the Cloudsche Luftschiff could be visited at the "Internationale

Luftschiffahrts-Ausstellung" (ILA) in Frankfurt/Main, next to constructions of

Zeppelin, Parseval and Ruthenberg.

During the numerous ascents during the exhibition visit, it turned out that the

control of the airship had to be modified.

Several provisional changes had already been made in Frankfurt, but only after

the return to Cologne the airship received a completely revised control system.

The

ship gained considerable maneuverability.

At the 1910 World Exposition in Brussels, the airship also undertook a trip,

where it completed several round trips and was awarded the prize for airships by

the flight committee of the exhibition. [38]

In total, the 'Clouth I' had carried out more than 40 trips, covering almost

2.000 kilometers;

This fact proved the operational safety and usability of this type.

A second airship was never developed, as the company Clouth is beginning to

withdraw from the area of air shipping as early as 1910. [39](interest

of military directed more into upcoming aeroplanes).

In addition to the construction of their own airships, there were also some

balloons from the Clouthian production, which have entered into the history of

aviation and pioneered. [40]

Cloudsche Luftschiff could be visited at the "Internationale

Luftschiffahrts-Ausstellung" (ILA) in Frankfurt/Main, next to constructions of

Zeppelin, Parseval and Ruthenberg.

During the numerous ascents during the exhibition visit, it turned out that the

control of the airship had to be modified.

Several provisional changes had already been made in Frankfurt, but only after

the return to Cologne the airship received a completely revised control system.

The

ship gained considerable maneuverability.

At the 1910 World Exposition in Brussels, the airship also undertook a trip,

where it completed several round trips and was awarded the prize for airships by

the flight committee of the exhibition. [38]

In total, the 'Clouth I' had carried out more than 40 trips, covering almost

2.000 kilometers;

This fact proved the operational safety and usability of this type.

A second airship was never developed, as the company Clouth is beginning to

withdraw from the area of air shipping as early as 1910. [39](interest

of military directed more into upcoming aeroplanes).

In addition to the construction of their own airships, there were also some

balloons from the Clouthian production, which have entered into the history of

aviation and pioneered. [40]

The art of ballooning spreads at the beginning of the 19th century.

Within and outside

Europe.

The downside, however, is that it was soon dominated mainly by fairgrounds with

their public ascents in open-air pools and less by inventors who were concerned

about technological advances.

In most cases ballooning was carried on by adventurers or members of the

fairground, but "a certain amount of authenticity had always adhered to their

actions."

[41]The exception to this, however, was France and England, where

private ascents were increasing and professional amateurs often accompanied them

or replaced by them [42]. The art of ballooning spreads at the beginning of the 19th century.

Within and outside

Europe.

The downside, however, is that it was soon dominated mainly by fairgrounds with

their public ascents in open-air pools and less by inventors who were concerned

about technological advances.

In most cases ballooning was carried on by adventurers or members of the

fairground, but "a certain amount of authenticity had always adhered to their

actions."

[41]The exception to this, however, was France and England, where

private ascents were increasing and professional amateurs often accompanied them

or replaced by them [42].

In the

course of the 19th and early 20th centuries, this

changesd

At this time, the balloon changed from a mere sight-seeing object to a sports

device, the development of the aerial sport "in the sense of a broad sport

accessible to everyone" [43].

Members of the upper social strata were now also discovering their practical

interest in ballooning.

The American James Gordon Bennett made an important contribution to the

development of this sport.

As a newspaper publisher, "on a constant search for a headline for his paper"

[44], he was financially supporting the development of aviation.

1906 started in Paris the international "Gordon-Bennett-race" for Freiballons

named, after him and successively took place annually, with an overwhelming

success.

The

effect of this air transport event was reflected in the form of a wave of

founding new clubs for airship. [45] Through the introduction of a balloon

license, the organization of competitions and balloon races as well as the

issuing of competition rules, these clubs contributed to the establishment and

popularity of ballooning. The first association in the Rhineland was the "Niederrheinische

Verein für Luftschiffahrt" (NVFL), founded on 15 December 1902. [46]

The founding of the "Cölner Aero-Club" took place in Cologne on 6 November

1906 at the Kattenbug 1-3 building, but it was already at the first general

meeting on 15 January 1907 the club

was renamed

"Cölner Club für Luftschiffahrt e. V." (CClL)

. [47]

The most important goals of the association were the establishment of airship in

educated circles as well as the exercise and maintenance of the aerial sport.

The founding members of the association were personalities from the domains of

economy, culture, society and the military.

The founding initiators included Dr. Cornelius Menzen, Hans Hiedemann, Dr Otto

Nourney, and a number of members of the "Cologne Automobile Club".

At the end of 1907

the CCfL already had 270 members.

Among them were well-known names such as Clouth, Greven and Stollwerck;

With 47 members, the officers form the largest professional group within the

club.

In 1908, the former student director of the Cologne College of Trade and

co-founder of the Cologne University, Prof. Christian Eckert, took over the

association presidency.

In 1910, the Cologne club recorded 700 members.On

February 9th, 1907, the first balloon launch of the club took place in Deutz.

All further ascents were from the youth playground at the Lindentor, the site of

today's Aachener Weiher.

The 7.750 m² area was equipped with 36 filling stations. [48]

First of all, the first balloon flights had to be undertaken together with other

balloon clubs and their ballooning centers, such as the Mid-Rhine and Airships

Association (Ballon 'Coblenz' or Ballon 'Barmen').

On April 6, 1907, the first club-like balloon, christened in the name of

'Cologne', had premiere.

On April 28, 1907, Hans Hiedemann was the first Cologne balloonist to receive

the ballooning license.

In the following years, Hiedemann became a successful balloon driver, he was

ranked third in the Gordon-Bennett race in St. Louis / USA on 21 October 1907.

Since the winner of this race, Oscar Erbslöh, was also a member of the CCfL, the

Cölner Club could celebrate one of its greatest triumphs in the first year of

its existence.

At

the same time the association demonstrated its high level.

At a similar event a year later, in 1908, in Berlin-Schmargendorf - "the largest Luftsportvereinigung, which Germany had experienced up to now" [49] - Hiedemann

had a misfortune with his rider, Dr. Niemeyer Glück: The balloon drivers in

Hiedemann's balloon 'Busley' made

the second-longest route with the second longest journey back, but the two

aeronauts between Norway and Scotland had to be on the high seas;

Only

after 26 hours were they saved by a ship.

Since the competition jury evaluated only landings, the merit of the two Cologne

residents was therefore disregarded. [50]

The CCfL soon had a large number of both, large and small airships and small

airships, which participated in numerous competitions and exhibitions.

In

1909, the Cologne club had numerous balloons;

Including five aerostats from Cologne-based Clouth - 'Clouth I to V', all of

which were available to the club. [51]

Since its foundation until 1914, the CCfL had recorded a total of 616 balloon

flights.

How committed the members of the CCfL were, is shown by the fact that the

Cologne club already in the second year of its existence, in 1907, had the

meeting of the "German Luftschiffer-Verband" (DLV), founded 1902 in Augsburg

byall aviation clubs.

The CCfL was included in DLV as the tenth club. [52]

For Cologne, the CCfL, founded in 1906, was the decisive starting point and

basis for a subsequent decades-long history of ballooning and aerial sports in

the city.

The general aviation industry in Cologne found a concrete form of organization:

"... as one of the most active airships in Germany, [the CCfL] carried out

numerous ballooning trips that represented great sporting activities and also

served scientific exploration of the atmosphere." [53]

Its members helped the sport at the beginning of its development to an immensely

great popularity within Cologne.

The practical exercise of the aerial sports initially covered open-air pools and

airships.

The impression of the new sport was so substantial and so enthusiastic about the

citizens of the cathedral that the events of the Cologne Club on the

balloon-lift-platform in front of the Lindentor always became events with a folk

festivity.

In the aftermath, the CCfL proved to be the organizer of important sporting

events. For Cologne, the CCfL, founded in 1906, was the decisive starting point and

basis for a subsequent decades-long history of ballooning and aerial sports in

the city.

The general aviation industry in Cologne found a concrete form of organization:

"... as one of the most active airships in Germany, [the CCfL] carried out

numerous ballooning trips that represented great sporting activities and also

served scientific exploration of the atmosphere." [53]

Its members helped the sport at the beginning of its development to an immensely

great popularity within Cologne.

The practical exercise of the aerial sports initially covered open-air pools and

airships.

The impression of the new sport was so substantial and so enthusiastic about the

citizens of the cathedral that the events of the Cologne Club on the

balloon-lift-platform in front of the Lindentor always became events with a folk

festivity.

In the aftermath, the CCfL proved to be the organizer of important sporting

events.

Cologne 1910

One of the highlights of the early history of ballooning was undoubtedly the "Internationale

Ballonwettfahrt" (International Balooning Competition)

organized by the Cologne club on June 27 and 29, 1909. Two Belgian and one Swiss

balloons were part of this biggest international competition before the First

World War.

The program of the first competition provided a balloon fox hunt with automotive

tracking.

35 gas balloons started to pursue the balloon 'Busley' with the balloon leader

Hans Hiedemann.

A red 'belly band' characterized his vehicle as a "foxballon".

On the

journey on June 29, 34 balloons took part.

During the preparations for the start, the Luftschiffer was supported by the

Airspeaker division stationed in Cologne.

Despite the rainy weather, there were thousands of people on the grounds around

the festival grounds.

The ascent place itself is less frequented by the spectators: participation in

the event was prohibitive for the majority of the population because of the high

entrance fees. [54]

The proceeds from the tickets sold did not cover the 16,000 marks raised by the

CCFL for the event.

For these and other reasons, the response to the event in the press was rather

subdued. [55]

The "Internationale Flugwoche" from September 30 to October 6, 1909, was the

second major sporting event of the year in Cologne.

The event, which was also the "most important sporting event in the field of

aviation in 1909," [56] took place on the Rennbahn (racecourse) in Cologne-Merheim,

[57] today's Weidenpesch.

For the first time it was possible for the Cologne population to experience the

new form of flying technology, the motorfliegerei (engine diven

flying Objects), directly.

The

interest in the event was correspondingly large.

During the event, French pilots with their French constructions dominated.

Famous aviation pioneers and art aviators, such as Louis Bleriot, Léon

Delagrange and Louis Paulhan, showed their avid skills, including Bl ériot,

a new speed record. [58] Airships, where an entry was given to numerous public

at the same time, were highly ériot,

a new speed record. [58] Airships, where an entry was given to numerous public

at the same time, were highly

frequented.

Experience with such events

had existed since 1909. [59]

The places used by the first pilots for such events were meadows or flat

terrain, so the flat lawn area of the Cologne horse race track was

particularly suitable for take-off and landing operations. [60]

The already mentioned dominance of French airplanes with French constructions

had the following reasons: At this time, France used considerable financial

resources for aircraft development and established itself as an air force in the

prewar years.

Unlike in Germany, aviation was mainly focused on the construction of airships,

especially the zeppelins.

Industry and, in particular, the military (apparently) underestimated the

capabilities of the aircraft and refrained from investing accordingly.

Germany was only trying to reach the level of French aviation in the coming

years. [61]

The resulting aircraft-related backlog was initially compensated in modest terms

by the involvement of private aircraft builders, as was the case in Cologne also

by Franz Clouth and later his sun Maximilian Clouth. frequented.

Experience with such events

had existed since 1909. [59]

The places used by the first pilots for such events were meadows or flat

terrain, so the flat lawn area of the Cologne horse race track was

particularly suitable for take-off and landing operations. [60]

The already mentioned dominance of French airplanes with French constructions

had the following reasons: At this time, France used considerable financial

resources for aircraft development and established itself as an air force in the

prewar years.

Unlike in Germany, aviation was mainly focused on the construction of airships,

especially the zeppelins.

Industry and, in particular, the military (apparently) underestimated the

capabilities of the aircraft and refrained from investing accordingly.

Germany was only trying to reach the level of French aviation in the coming

years. [61]

The resulting aircraft-related backlog was initially compensated in modest terms

by the involvement of private aircraft builders, as was the case in Cologne also

by Franz Clouth and later his sun Maximilian Clouth.

One of the first Cologne flight pioneers in this area was Arthur Delfosse.

Since 1902, the Cologne-born self-constructions had been built, the

flightability of which, as usual, did not initially go beyond a few hops.

This year, the first air leaked on the Mülheim heath.

In addition to Arthur Delfosse, Bruno Wernbgen, Jean Hugot and others, who

were particularly meritorious in the field of motorfliegerei, and who therefore

occupied a special position within Cologne's aviation history. [62]

The "International Ballonwettfahrt" and the "Internationale Flugwoche" from 1909

undoubtedly represented the highlights of Cologne's history of aerial sports.

The number of a total of 69 ascents during the balloon contest underpined the

position of the open-air pool as a traditional aircraft and put it at the center

of Cologne's sporting interest.

At the same time, the "Internationale Flugwoche", with the demonstrations of the

first Motorflieger, began the start of further such flights in the city of

Cologne. From this point on, the Motorfliegerei enjoyed a growing popularity

within the cathedral city.

This enthusiasm could be seen in an event in 1911. The "Grand Schaufliegen"

(air display) in Cologne on 19 June this year was a pure

motor-flying event. The venue was like two years earlier the race track in

Cologne-Merheim.

The decking was also the eighth day stage of the "1.

German Round Trip - 'B.

Z. - Preis der Lüfte '. [63] This Cologne event did form part of the largest

motor flight event of this kind before the First World War.

Now also a few Kölner Flieger were represented, above all Bruno Wernberg

impressed with his successful flights.

In the same year the Frenchman Adolphe Pégoud organized another flight day at

the same place; The cologne

people came to thousands.

The terrain of the horse racing track in the north of Cologne represented a

provisional place for such events. Since the balloon drivers with the terrain at

the Lindentor already had an ascent space tailored to their needs, the Cologne

Motorflieger intended to set up a suitable place for their aerial sports

activities.

The

search for such an airfield began as early as 1908.

For the time being, this project failed at the military authority, which, up

to that point, had not been able to make a decision because of the fortress

character of the cathedral city [64].

In 1910, some of Jean Hugot's flight experiments took place on the farm of the

Butzweiler farm.

By and by, other Cologne flyers use the good take-off and land characteristics

of the area and, as Hugot before, had permanent shelters for their aircraft.

The first serious attempts on the part of the city administration to set up an

airfield permanently in Cologne took place in 1911. Although the area around the

still existing agricultural enterprise of the Butzweiler Hof was planned as a

future landing and launching place, the final accommodation of the airfield was

planned.

This body was in no way decided. [65]

In the autumn of the year, the CCfL negotiated with the city about the leasing

of a larger urban land property north-west of today's Cologne district of

Volkhoven, in order to set up an airfield there.

Meanwhile, however, the German military had also become aware of the military

importance of the aircraft and would use it harshly in the upcoming world war I.

II. 2 Military ballooning and airships

The first direct testimony of a balloon rose in Cologne was the ink drawing by

Franz Xaver (?) Laporterie [68] entitled "View at the Hahnenpforte on June 29,

1795, since the French balloon is omitted".

The drawing

shows the area before the Hahnentor.

In the foreground of the picture are the outer walls of the city fortification

in Cologne, in the right half of the picture a part of a fortress tower is

visible.

From the

city, a path leads out into the open terrain.

On this, in the presence of a large group of spectators, a tethered balloon is

released.

Beneath the actual balloon, the gondola of the balloon is recognizable in the

form of a gondola, in which three persons can be seen.

Further spectators are at the beginning of the road and on the outer walls of

the fortified walls.

The event of the French balloon flight, which marked the beginning of the manned

airship in Cologne, was confirmed by another source: this was a letter from a

Balthasar Kourt dated 15 July 1795 to the imperial city of Cologne under French

administration. [69]

In this, Kourt demanded reparation for the damage that arose in the field caused

by the abandonment of a balloon.

Decisively determined by

Ferdinand Graf (Count) von Zeppelin, using airships is carried

out at the beginning of the 20th century.

The

development of "dirigibles", so-called Zepplin airships.

On July 2, 1900 the Count of Zeppelin succeeded in a controlled trip with the

128 m long airship 'LZ 1', which he designed.

A new path

in aviation is being pursued.

The journeys that had so far been made with the balloons were random flights.

Only the invention and the use of the gasoline engine allowed the controlled, no

longer spherical, but streamlined airships a controlled movement through the

airspace.

The 'LZ 1' was followed by further rigid airships by Count Zeppelin.

In May 1906 he submitted an offer to the German Ministry of War to sell his

entire airship production to the state.

In particular, he emphasized the advantages of the airship in mobilization by

means of an attached study. [74]

The Luftwaffe disaster of the LZ 4, in August 1908 in Stuttgart-Echterdingen,

did not mean the end of German airships.

On the contrary, in a few months, more than 7 million marks were donated to the

progress and the technical development of the airship of citizens by a national

enthusiasm.

The high sum of this "Zeppelinspende" (Zeppelin Donation)

showed that in this time the Graf Zeppelin could be certain with his invention

of a large support in the population. Decisively determined by

Ferdinand Graf (Count) von Zeppelin, using airships is carried

out at the beginning of the 20th century.

The

development of "dirigibles", so-called Zepplin airships.

On July 2, 1900 the Count of Zeppelin succeeded in a controlled trip with the

128 m long airship 'LZ 1', which he designed.

A new path

in aviation is being pursued.

The journeys that had so far been made with the balloons were random flights.

Only the invention and the use of the gasoline engine allowed the controlled, no

longer spherical, but streamlined airships a controlled movement through the

airspace.

The 'LZ 1' was followed by further rigid airships by Count Zeppelin.

In May 1906 he submitted an offer to the German Ministry of War to sell his

entire airship production to the state.

In particular, he emphasized the advantages of the airship in mobilization by

means of an attached study. [74]

The Luftwaffe disaster of the LZ 4, in August 1908 in Stuttgart-Echterdingen,

did not mean the end of German airships.

On the contrary, in a few months, more than 7 million marks were donated to the

progress and the technical development of the airship of citizens by a national

enthusiasm.

The high sum of this "Zeppelinspende" (Zeppelin Donation)

showed that in this time the Graf Zeppelin could be certain with his invention

of a large support in the population.

On the initiative of the CCfL, the city of Cologne was asked to provide

Zeppelin, the first German city, with an airship hall with technical facilities.

[75]

The Cologne citizenship in 1908 corresponded to the efforts of the Cologne

citizenship in the form of a financial participation in the newly founded German

airship A. G. in Frankfurt am Main (DELAG), [76] the world's first air transport

company.

The purpose of the company was to carry out scheduled air transport with

airships: "These ships should not, of course, carry out regular traffic, for

example by rail, but were intended for occasional amusement trips ..." [77]

Although Cologne is concerned with the integration of the airship ship into the

DELAG-Luftverkehr ", the" majority of the members of the DELAG Supervisory

Board meeting of 28 February 1910 decided in favor of Düsseldorf. "[78]

In

the late summer of 1909, the Zeppelin fever reached the cathedral city.

On the 5th of August, LZ 5, arriving from ILA in Frankfurt on Main, arrived in

Cologne at about 11.30 am. [79]

"The enthusiasm of the Cologne people, who have never seen a zeppelin, knows

no bounds: already in the early morning countless people make their way to

Bickendorf ... Also in other places, for example, in front of the cathedral or

on the hill near Müngersdorf

Many Cologne to see the 'flying cigar' at the approach.

The Cologne 'Pänz' even gets schulfrei. "[80] Before his landing in

Bickendorf, the 136 m long LZ 5, personally controlled by Count Zeppelin,

traveled twice the towers of the Cologne Cathedral and presented itself to the

citizens of Cologne.

At the Landeplatz in Cologne-Bickendorf a huge, cheering crowd received Count

Zeppelin and his team.

A

memorandum on an oriel of Herwarthstr.

31, where Graf Zeppelin spent the night, still recalls this visit. In

the late summer of 1909, the Zeppelin fever reached the cathedral city.

On the 5th of August, LZ 5, arriving from ILA in Frankfurt on Main, arrived in

Cologne at about 11.30 am. [79]

"The enthusiasm of the Cologne people, who have never seen a zeppelin, knows

no bounds: already in the early morning countless people make their way to

Bickendorf ... Also in other places, for example, in front of the cathedral or

on the hill near Müngersdorf

Many Cologne to see the 'flying cigar' at the approach.

The Cologne 'Pänz' even gets schulfrei. "[80] Before his landing in

Bickendorf, the 136 m long LZ 5, personally controlled by Count Zeppelin,

traveled twice the towers of the Cologne Cathedral and presented itself to the

citizens of Cologne.

At the Landeplatz in Cologne-Bickendorf a huge, cheering crowd received Count

Zeppelin and his team.

A

memorandum on an oriel of Herwarthstr.

31, where Graf Zeppelin spent the night, still recalls this visit.

The journey from 'LZ 5' on 5 August 1909 served its transfer to a military

advance command, which was located since April 1909 in the fortress Cologne and

/ or in Cologne-Bickendorf and prepared for the handover.

The airship was given the military designation 'Z II'; as an army ship, it was

to take over mainly reconnaissance and observation tasks.

In the same month, the four months of construction work on the airship landing

stage and the airship port were under the auspices of the military construction

authority.

Between the present Venloer Straße and the Ossendorfer Weg an airship hall was

built.

The construction work was carried out by Gustavsburg Pottgen, the building

contractor based in Cologne-Ehrenfeld, at the Gustavsburg factory in Mainz, the

machine factory and bridge building "Augsburg-Nürnberg AG". [81]

83]

Buildings for teams and workshops were built in the immediate vicinity of the

hall.

In the course of the construction work at the airship port in Cologne-Ehrenfeld

a hydrogen gas station of the municipal gas works, which served the refueling of

the airship.

The airship hall of the Cologne airship harbor was designed as a 'driving and

rescue hall'.

It corresponded to the hall plan and type of a so-called 'fixed, single-nave

longitudinal hall' and had a single hall opening at the head of the building,

although such a hall should 'be better equipped with gates on both gables' [84].

The fact that the military decided for this type of hall can be explained as

follows: The construction of Längshallen (long halls) is the simplest and

cheapest compared to the "other" halls.

The longitudinal hall was therefore the most common and usual form of the

airship hall. "[85] The airship hall of the Cologne airship harbor was designed as a 'driving and

rescue hall'.

It corresponded to the hall plan and type of a so-called 'fixed, single-nave

longitudinal hall' and had a single hall opening at the head of the building,

although such a hall should 'be better equipped with gates on both gables' [84].

The fact that the military decided for this type of hall can be explained as

follows: The construction of Längshallen (long halls) is the simplest and

cheapest compared to the "other" halls.

The longitudinal hall was therefore the most common and usual form of the

airship hall. "[85]

The buildings of the airship ship can be summarized as follows: In the exterior,

the airship hall was a long, elongated, rectangular building. It was 152 m long

and 50 m wide, the hall opening had a clear height of 27.5 m.

On both sides there were low, lateral extensions along the entire length of the

hall with a piled roof.

Two- and three-part windows with upper round edges were used as the exposure of

this hall area, in which some of the workshops were located.

The entrance into the hall was also possible via wing doors, also round-arched.

Large, rectangular windows were cut into the side walls and the roof slopes (of

the elevated hall area) of the actual hall.

The roof

was similar to the shape of a mansard gable.

Three triangular roof superstructures had been drawn in as three-seater roof

trusses along the roof. [86]

The hall

had a steel structure as a support with the advantage of an overall smaller

outer dimension compared to halls of wood or reinforced concrete and a smaller

wind attack area. The hall lining consisted of large interconnected metal

tracks. The hall

had a steel structure as a support with the advantage of an overall smaller

outer dimension compared to halls of wood or reinforced concrete and a smaller

wind attack area. The hall lining consisted of large interconnected metal

tracks.

The hall gate was a combined swivel and swing gate, that was a folding door

[87], which was inserted into a rectangular steel frame in front of the hall by

means of guide rollers. The combination of an internal swivel and an external

turntable was a technically sophisticated design. The drive of the hall gate

mechanism took place exclusively at the bottom of the inside of the rotary door,

the swinging door ran by itself. The passing airship thus received adequate wind

protection. Thus the most important task was to "open and close the halls in

a short time for the entry and exit of an airship" [88].

The entire building complex of the airship harbor ran as a spatial separation

from the surrounding terrain, a fencing in the form of a wall. Since the airship

was only a hall opening to the entrance and exit was available, approximately

one kilometer away from the hall a device for anchoring the airship was installed.

The ship could be installed there in the event of an unfavorable weather

situation, in order to drive it into the hall.

In August 1909 the "Reichsluftschiffhafen Cöln" [89] was opened and used as a

Zeppelin airport for military purposes.

The first order of the Lufschiffer battalion No. 1, which was now stationed in

the Cologne Reichslufthafen, was followed two years later by further units.

On October 1, 1911, both the seat of the staff and the 1st Company of the newly

formed Battalion No. 3 battalion were transferred to the cathedral city.

The unit was provisionally lodged at Bocklemünd, Fort IV of the Prussian

fortress ring around Cologne. [90]

In the following years, an air raid barracks was built at Frohnstraße 190 in

Cologne-Ossendorf.

Many

air traffic controllers joined the CCfL as active members.

Between the Luftschiffer battalion and the Cologne club, close contacts were

soon established, which meant that "in the early years" a successful

civil-military cooperation had been practiced "[91].

The friendly cooperation had the advantage for the association, for example,

that the CCfL balloons may have been filled free of charge with the light gas

discharged from the airship.

The unit, which had been renamed "Luftschiffer-Abteilung" since 1887, served as

a model for the Luftwaffe battalions, which were soon to be established, and the

later Lufschiffer battalions. "[190] Between 1909 and 1912,

Autumn airship maneuvers took

place. [93]

In addition to the Zeppelin airships, which were part of the rigid construction,

there were also the semi-armed airships of Major Hans Gross with the designation

'M' as well as the non-rigid impact airships with the designation 'P', which

were designed by Major August von Parseval . [94]

The aim of these maneuvers was the field trial of the military airships of all

three types of construction.

Above all it was about the determination of the achievable maximum height.

Observed were the test journeys of emissaries of the military commission of

the Prussian army administration.

One of the largest airship maneuvers was in Cologne from 25 October to 20

November 1909. [95]

The three military airships 'Z II', 'M II' and 'P II' as well as the private

airship 'P III' completed journeys of various kinds: speed, low and high rides

as well as formation, relay and night drives.

During the entire duration of the maneuver, the airship hall in Cologne-Bickendorf

was surrounded by spectators and rapporteurs from domestic and foreign

newspapers.

The last maneuvering of all four airships together took place on 6 November 1909

over Cologne.

The

spring maneuvers of 1910 began on the 7th of April.

In addition to the military airships 'Z II', 'M II' and 'P II', the Cologne

airship 'Clouth' and the 'Erbslöh' airship from Leichlingen also participated as

guests.

In the course of the maneuver 'Z II' stranded on 24 April 1910 near Weilburg a.

d. Lahn and was destroyed by a storm on the ground.

It had

torn itself out of its anchorage the day before.

The resulting damage to the airship was irreparable.

After a total of 16 journeys (2478 km) 'Z II' was scrapped. [96]

On November 23, 1911, the Zeppelin airfield 'Z II' [97] (LZ 9) transferred

personally from Friedrichshafen to Cologne reached the cathedral city.

The airship arrived with a considerable delay to the airship maneuver already

taking place since the beginning of November.

The military were disappointed by the results so far of the maneuvers, which

also included the military airship 'M II'.

Also the hope that the participation of '(replacement) Z II' would develop the

airship maneuvers better was not fulfilled due to the bad weather;

The maneuver ended in early

December.

In the opinion of the military, the successes were in no relation to the

expectations.

The airship '(replacement) Z II' was stationed in the fortress city of Cologne

after completion of the airship maneuver.

The status of the cathedral city as a fortified city and at the same time as the

location of a military airship port brought with it numerous problems for the

general civil aviation and in particular for the interests of the civilian

Cologne aviation.

Since 1911, the Cologne fortress governor had prohibited the city from flying

over and photographing the city. [98]

The background of the prohibition was the fear that by enemy agents the terrain

could be spied.

For example, the airship 'Ersatz-Deutschland' (LZ8) on its journey to Düsseldorf

on 12 April 1911 had to avoid the fortified city of Cologne.

The Zeppelin passenger airships were not permitted to fly over and landings

within the boundaries of the city.

Cologne was thus excluded from the new lines of DELAG air transport. [99]

The danger, however, that the CCfL would have to dissolve because of this

prohibition did not exist.

The fortress governor made a big concession to the members of the CCfL: In the

fortress area of Cologne they were still allowed to climb in the open air and

on the airplane. [100]

Thus, the exercise of the aerial sport within the cathedral city remained at

least for the members of the CCfL.

However, this exemption did not apply to private pilots or companies which

operate the aviation business.

During the course of 1911/12 the German military leadership recognized the

inadequate effectiveness of the airships as a weapon in the air warfare: "According

to the present situation, airships can do some service in the war of leadership,

less as a weapon than in the Enlightenment."

] At the beginning of 1912, the Ministry of War decided to accelerate the

construction of the Army Air Force group.

With a "national flight donation" the German citizens were called upon to

support the development of the aircraft financially.

From 1911 onwards, the Cologne military administration looked back on the

construction of a civilian airport and, in accordance with the plans of the

Ministry of War, pursued the construction of a military air base. [102]

1912 between the city of Cologne and the Reichsfiskus a contract concluded, the

lease and military use of a site at the Butzweiler Hof to 20 years.

The site "is particularly favorable because it is directly adjacent to the

military airship hall built in Ossendorf." [103] The military took over the

installation of the rolling-field and the construction of the airfield

facilities.

The city ensured the creation of a tram connection.

In order not to completely exclude a civilian use of the terrain, the CCfL

encouraged, in agreement with the commander of the air base station, to carry

out flight events on the pitch. [104]

On September 15, 1912, the foundation stone was laid for the military flying

station "Butzweiler Hof".

The military advance, which arrived on December 1, 1912, without airplanes in

Cologne, began with the first work on the installation and construction of a

military air station

III.

Concluding remarks

The historical history of the conquest of the airspace can be clearly

illustrated by the early history of aviation in Cologne;

It proves to be very versatile, so the different facets of the balloon can be

found, for example, as an attraction as well as a sports device; later it is the use of the airships for military purposes as well as the

beginning of the motor-yachting.

As early as the 18th century, only a few years after the successful start of a

Montgolfiere, the rise of a manned balloon can be demonstrated in Cologne. On

June 29, 1795, a military observation balloon was opened by French troops at the

gates of the city.

In the course of the 19th century,

numerous

balloon ascents took place in the cathedral city, such as by the airmen Sinval

and Guerin in 1808 and 1847 by the famous balloon driver Charles Green.

During this period, the French and English were the ones who visited the

cathedral city and show balloon ascents.

Spectacular balloon ascents took place at the end of the 19th century.

In the so-called

"golden corner" (Pub "Goldenes Eck") in Cologne-Riehl.

As a permanent attraction, the Aeronaut Maximilian Wolff ran balloon flights

with passengers for commercial purposes.

Around the turn of the

19th / 20th century,

The "Cölner Aero-Club", the later "Cölner Club für Luftschiffahrt e. V."

(Cologne's club for aviation) was celebrated in Cologne on November 6,

CCfL).

This laid the foundations for the development of aerial sports within the Rhine

metropolis.

In addition, Cologne was an important impetus for the development of balloon and

zeppelin technology: the Cologne-based company Clouth developed a steerable,

motor-driven airship (Dirigible) in 1907.

The airship hall built in this context can also be viewed as the first air

traffic architecture in Cologne.

The

year 1909, with the "International balloon competition" and the

"International flight week", highlights the beginnings of Cologne's aviation

history.

This year, the citizens of Cologne was able to experience and admire aircraft

for the first time at such an event.

Venues Cologne's aerial sports activities were initially the site of today's

Aachener Weiher as well as the horse racing course in today's Cologne-Weidenpesch. The

year 1909, with the "International balloon competition" and the

"International flight week", highlights the beginnings of Cologne's aviation

history.

This year, the citizens of Cologne was able to experience and admire aircraft

for the first time at such an event.

Venues Cologne's aerial sports activities were initially the site of today's

Aachener Weiher as well as the horse racing course in today's Cologne-Weidenpesch.

In the same year, the military interests in aviation emerged in the fortified

city of Cologne in the founding and installation of an airship harbor in

Cologne-Bickendorf as well as the stationing of a military airship.

The airship hall erected here was one of the very first architectural features

of an air transport architecture in the Cologne city area and was also a

remarkable engineering achievement of this time.

In the following years, Cologne was location of numerous airship maneuvers.

Although the fortified character of the city was hampered by a further expansion

of the city's aerial sports by flying and photographing bans, there was

civil-military cooperation between the CCFL and the stationed battalion

battalion;

The inclusion of Cologne in a national airship network was prevented by the

military regulations.

1912

was the year of foundation for the military flight station "Butzweiler Hof"

and at the same time the starting point for all other aviation ambitions in

Cologne.

In summary, it should be noted that the events of the early years of Cologne

aviation were also revealing with regard to general aviation. The events of

civilian and military aviation, cited in Cologne, certainly document a very

small section of the general German aviation history. They were, however,

very representative, for they show the development of general aviation in

Germany up to the beginning of the twentieth century. comprehend.

[1]

ECKERT, Alfred: Zur Geschichte der Ballonfahrt. In: Leichter als Luft, 1978, S.

15–133, hier S. 67 (= Ausst.-Kat. Leichter als Luft. Zur Geschichte der

Ballonfahrt. 24.09.–26.11.1978 Westfälisches Landesmuseum für Kunst- und

Kulturgeschichte, bearb. von Bernard Korzus. Greven 1978). Eine Ausnahme unter

den deutschen Landesherren ist der wissenschaftlich interessierte Herzog von

Braunschweig. Auf dessen Veranlassung wird ein Gasballon konstruiert, der am

28. Januar 1784 in Braunschweig aufsteigt.

[2]

Vgl. ECKERT (1978), S. 67.

[3]

Vgl. ECKERT (1978), S. 84.

[4]

Vgl. ECKERT (1984), S. 84. Die Rundreise in Deutschland umfaßt insgesamt 10

Städte; weitere Stationen sind u. a.: Hamburg (23. August 1786), Leipzig (29.

September 1787), Nürnberg (12. November 1787), Braunschweig (10. August 1788),

Wien (9. März.1791, mißglückter Start); erst mit Blanchards Abreise nach

Amerika 1792 enden diese Vorstellungen.

[5]

Vgl. MAYER, Edgar, MÜLLER-AHLE, Monika: o. T. - Unveröff. Typoskript. o. D;

SUNTROP, Heribert: Der Butzweilerhof und die Kölner Luftfahrt. Chronik. Eine

Arbeitsgrundlage für die Geschichtsschreibung. Unveröff. Typoskript, Bd. 1.

2001.

[6]

Vgl. HAStK, Best. Ratsprotokolle, Nr. 232; MAYER, MÜLLER-AHLE (o. D.), S. 2.

[8]

Vgl. MAYER, MÜLLER-AHLE

(o. D.), S. 2.

[9]

Vgl. VOGT, Hans: Seidene Kugel und Fliegende Kiste. Eine Geschichte der

Luftfahrt in Krefeld und am Niederrhein. Krefeld 1993 (= Krefelder Studien, Bd.

7, hrsg. vom Stadtarchiv Krefeld), hier S. 11. Bereits Anfang 1785 erfolgt in

Düsseldorf ein Aufstieg einer Charlière.

[10]

Entweder handelt es sich um einen dreimaligen Aufstieg eines einzigen Ballons

oder um einen einmaligen Aufstieg von insgesamt drei Ballonen. Ob diese

Ballonaufstiege mit oder ohne menschliche Besatzung stattfinden, ist nicht mehr

eindeutig zu klären.

[11] Vgl.

Cölnischer Staatsboth, 13. Junius 1788, 73tes Stuck und 4. Julius 1788, 83tes

Stuck; MAYER, MÜLLER-AHLE (o. D.), S. 3.

[12]

Deutz ist Bestandteil der Stadterweiterung Kölns von 1888; erst seitdem ist es

Stadtteil der Rheinmetropole.

[13] Die Aussicht

auf wirtschaftlichen Profit durch zahlende Zuschauer scheint die anfänglich

ablehnende Haltung des Kölner Erzbischofs und Kurfürsten revidiert zu haben.

[14]

Vgl. Rheinischer Merkur, 24. Juli 1911; MAYER, MÜLLER-AHLE (o. D.), S. 3.

[15] ECKERT (1978), S. 86.

[16] ECKERT (1978), S. 105.

[17] Vgl. Gazette de Française de Cologne, 20.

April 1808, 8. Mai 1808, 14. Mai 1808; Der Verkündiger 24. April 1808,

Nr. 581, 1. Mai. 1808, Nr. 583; MAYER, MÜLLER-AHLE (o. D.), S. 7.

[18]

Vgl. ECKERT (1984), S. 104; MACKWORTH-PRAED, Ben: Pionierjahre der Luftfahrt.

Stuttgart 1993, hier S. 54. Charles Green (1785-1870) gehört zu den

berühmtesten Ballonfahrern seiner Zeit. Ihm sollen über fünfhundert Aufstiege

gelungen sein. Besondere Verdienste kommen ihm für die Weiterentwicklung des

Ballons durch Einführung des Kohlenstoffgases zu. Green beschränkte sich in

seiner Luftfahrertätigkeit nicht ausschließlich auf Schaufahrten, sondern

verband damit auch wissenschaftliche Ambitionen.

[19]

Vgl. Rheinischer Beobachter, 2. Mai 1847, Nr. 153; MAYER, MÜLLER-AHLE (o. D.),

S. 7.

[20]

Vgl. HStA Düsseldorf, Best. Polizeipräsidium Köln, Nr. 49 (Schreiben von

Gustave Landreau an den Polizeipräsidenten von Köln vom 19. März 1878); MAYER,

MÜLLER-AHLE (o. D.), S. 7.

[21] Vgl. HOHMANN,

Ulrich: Beiträge zur Geschichte des Ballonsportes in Deutschland. Die Zeit von

1900 bis 1939, Bd. 1 (hrsg. vom Deutschen Freiballonsport-Verband e. V.). o. O.

1993, hier S. 8. Später wird der Verein in „Berliner Verein für Luftschiffahrt

e. V.“ umbenannt.

[22]

Vgl. HStA Düsseldorf, Best. Polizeipräsidium Köln, Nr. 49 (Briefkopf eines

Schreibens bzw. Schreiben von Maximilian Wolff an den Polizeipräsidenten von

Köln, 6. Juni 1889 und 7. Juni 1890); MAYER, MÜLLER-AHLE (o. D.), S. 8.

[23]

Der sog. altkölnische Festplatz zwischen Flora und dem zoologischen Garten wird

vom Volksmund wegen der vielen Vergnügungsgärten das „Goldene Dreieck“ genannt.

[24]

Vgl. DIETMAR, Carl: Die Chronik Kölns. Dortmund 1991, hier S. 273. Die

Ausstellung dauert vier Monate an und findet im Vergnügungspark „Kaisergarten“

des „Goldenen Dreiecks“ statt.

[25]

Vgl. Kölner Local-Anzeiger, 11. Juni 1889, Nr. 56; MAYER, MÜLLER-AHLE (o. D.),

S. 9.

[26]

Die Ausstellung dauert vom 16. Mai bis 15. Oktober 1889 an und findet im

heutigen nördlichen Teil des Zoologischen Gartens, in Nähe der Flora, statt.

[27]

Vgl. Kölner Local-Anzeiger, 11. Juni 1889, Nr. 56; MAYER, MÜLLER-AHLE (o. D.),

S. 9.

[28]

Vgl. Kölnische Nachrichten, 9. Juli 1890, Nr. 154; MAYER, MÜLLER-AHLE (o. D.),

S. 10.

[29]

Vgl. SUNTROP (2001), S. 9; Diese Ereignisse vom 7. Juli 1890 werden in 27

weiteren Zeitungen in ganz Deutschland veröffentlicht.

[30]

Vgl. HStA Düsseldorf, Best. Polizeipräsidium Köln, Nr. 49; MAYER, MÜLLER-AHLE

(o. D.), S. 11.

[31] Vgl. SUNTROP (2001), S. 10.

[32] Vgl. VOGT (1993), S. 24–32.

[34]

Vgl. Rheinisch-Westfälische Zeitung, Nr.1238, 27. Juni 1910; MAYER, MÜLLER-AHLE

(o. D.), S. 8.

[35] Vgl. MACKWORTH-PRAED (1993), S. 83.

[36] Vgl. FRANZ CLOUTH. RHEINISCHE

GUMMIWARENFABRIK AG (Hrsg.): 90 Jahre Franz Clouth. 1862-1952. Köln o. D., hier

S. 13. Die Firma Clouth liefert u. a. 1899 den Ballonstoff für das erste

Luftschiff des Grafen Zeppelin ‘LZ 1’.

[37]

Vgl. FRANZ CLOUTH (o. D.), S. 14. Der Bau besteht mindestens bis 1912. Aus

welchem Material die Halle besteht, ist nicht zu sagen; sie brennt Jahre später

ab.

[38]

Vgl. CLOUTH GmbH, Firmenarchiv, Liste der Zeitungsartikel im Zusammenhang mit

der Brüsselfahrt des Luftschiffes ‘Clouth’ vom 20. Juni 1910. An dieser Stelle

bedankt sich der Autor bei Herrn Wolfgang Beier, der u. a. das Archiv der

„Clouth GmbH“ leitet, für seine Hilfe und zahlreichen Hinweise.

[39]

Vgl. CLOUTH GmbH, Firmenarchiv (Liste der angefertigten Bauteile). Einige

Dokumente im Archiv der Firma „Clouth“ belegen jedoch die Absicht vom Bau eines

zweiten Luftschiffes. Obwohl bereits verschiedene Bauteile angefertigt wurden,

wurde die Konstruktion anschließend nie abgeschlossen.

[40]

Vgl. FRANZ CLOUTH (o. D.), S. 13.

[41]

MAYER, MÜLLER-AHLE (o. D.), S. 12.

[42]

MACKWORTH-PRAED (1993), S. 51.

[43]

MAYER, Edgar: Glanzlichter der frühen Luftfahrt in Köln. 75 Jahre

Butzweilerhof. Oldenburg 2001 (= Luftfahrtgeschichte von Köln und Bonn, Bd. 1,

hrsg. von der Fördergesellschaft für Luftfahrtgeschichte im Kölner-Raum e. V.),

hier S. 89.

[44]

HOHMANN (1993), S. 12.

[45]

Vgl. HOHMANN (1993), S. 53. Dort ist eine nach dem jeweiligen Gründungsdatum

chronologisch angeordnete Liste der Vereine (bis 1910) zu finden.

[46]

Vgl. HOHMANN (1993), S. 11; VOGT (1993), S. 32–36.

[47]

Vgl. KÖLNER KLUB FÜR LUFTSPORT e. V. (Hrsg.): Festschrift zum 75jährigen Bestehen

des Kölner Klub für Luftsport e. V. Köln o. D, hier S. 17.

[48]

Vgl. MAYER, MÜLLER-AHLE (o. D.), S. 14; KÖLNER KLUB FÜR LUFTSPORT e. V. (o.

D.), S. 17.

[49]

HOHMANN (1993), S. 12.

[50]

Vgl. HOHMANN (1993), S. 120/121.

[51]

Vgl. STADE, Hermann (Hrsg.): Jahrbuch des Deutschen Luftschiffer-Verbandes

1911. Berlin 1911, hier S. 150/151.

[52]

Vgl. HOHMANN (1993), S. 53.

[53]

MAYER (2001), S. 18.

[54]

Preise, jeweils Tageskarte: Korbplatz/Herren 10, Damen 8 und Kinder 4 Mark;

Promenadenplatz/5, 3 und 1,50 Mark; Rasenplatz/alle 0,75 Mark. Der Stundenlohn eines beispielsweise Kohlentransportarbeiters beträgt 0,43

Mark.

[55]

Vgl. Rheinische Zeitung, 22. Juni 1909, Nr. 141 und 26. Juni 1909, Nr. 145;

MAYER, MÜLLER-AHLE (o. D.), S. 17.

[56]

Vgl. das „Fest-Programm zur grossen internationalen Flug-Woche, Cöln am Rhein

vom 30. September bis 6. Oktober 09“.

[57]

Bisweilen ist auch die Schreibweise mit doppeltem „e“ – „Meerheim“ sowie mit

„h“ – „Mehrheim“ – zu finden.

[58]

Blériots Geschwindigkeitsrekord liegt bei ca. 60 km/h.

[59]

Die erste bedeutende Veranstaltung findet am 23. Mai 1909 auf dem Flugfeld

Port-Aviation, südlich von Paris, statt.

[60]

In Johannisthal, südöstlich von Berlin, werden 1909 bzw. 1908 beispielsweise

von den Pferderennbahnen Holztribünen übernommen; in Brookland/England finden

ab 1909 die Flugschauen unweit der 1907 gebauten Rennstrecke statt.

[61]

GÄRTNER, Ulrike: Flughafenarchitektur der 20er und 30er Jahre in Deutschland.

Diss. Marburg/Lahn 1990, hier S. 11: „Inoffiziell beschäftigte sich aber auch

das deutsche Militär seit 1909 mit der Konstruktion eines Flugzeugs.“

[62]

Eine eingehende Darstellung der Kölner Flugpioniere kann im Rahmen der

vorliegenden Ausführungen nicht geleistet werden. Dazu bedarf es einer

eigenständigen Schilderung, um diesem Kapitel Kölner Luftfahrtgeschichte gerecht

zu werden.

[63]

Die Veranstaltung beinhaltet Preise in Höhe von 100000 Mark, gestiftet von der

Berliner Zeitung/Ullstein-Verlag, sowie Geldpreise des Preußischen

Kriegsministeriums, von Flugsportvereinen, Städten und Gemeinden. Bei dieser

Veranstaltung, bei der nur deutsche Flieger zugelassen sind, werden insgesamt

13 Tagesetappen mit 1854 km zurückgelegt.

[64]

Vgl. DIETMAR (1991), S. 228. Zu Beginn der preußischen Herrschaft wird Köln von

König Friedrich Wilhelm III. zur Festung erklärt.

[65]

Vgl. SUNTROP (2001), S. 54. Die Stadt beabsichtigt den bestehenden Pachtvertrag

mit dem Landwirt des Butzweiler Hofs zu kündigen, um

das Feld uneingeschränkt für die Fliegerei zur Verfügung zu stellen.

[66]

Vgl. SUNTROP (2001), S. 60.

[67]

Vgl. SUNTROP (2001), S. 65.

[68]

Vgl. THIEME, Ulrich, BECKER, Felix: Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler,

22. Bd. (Krügner-Leitch). Leipzig 1928, S. 377. Bei dem Künstler handelt es

sich vermutlich um Franz Xaver Laporterie (geb. 1754 in Bonn, gest. ?), dem ersten Sohn von Peter Laporterie. Franz Xavers

künstlerische Tätigkeit in Köln - vorwiegend als Stecher - ist dort seit 1780

bezeugt.

[69]

Vgl. HAStK, Best. Franz. Verw., Nr. 5012; MAYER, MÜLLER-AHLE (o. D.), S. 4.

[70] Vgl. LOCHER,

Walter: Militärische Verwendung des Ballons. In: Leichter als Luft, 1978, S.

238–250, hier S. 238 (= Ausst.-Kat. Leichter als Luft. Zur Geschichte der

Ballonfahrt. 24.09.–26.11.1978 Westfälisches Landesmuseum für Kunst- und

Kulturgeschichte, bearb. von Bernard Korzus. Greven 1978).

[71]

LOCHER (1978), S. 243.

[72]

Vgl. SUNTROP (2001), S. 3. Der „Revue- und Schiessplatz“ Wahner Heide wird im

Frühjahr des Jahres 1817 auf Weisung des preußischen Königs Friedrich Wilhelm

III. angelegt. In den nachfolgenden Jahren wird der Übungsplatz immer wieder

vergrößert.

[73]

Zur allgemeinen Kennzeichnung der deutschen Luftschiffe: LZ =

Zeppelin-Luftschiff; PL = Parseval-Luftschiff. Militärluftschiffe tragen

zunächst ein „Z“, später zusätzlich ein „L“ vor der Ordnungsnummer.

[74]

Vgl. SCHMITT, Günter: Als die Oldtimer flogen. Die Geschichte des Flugplatzes

Johannisthal. Berlin (DDR) 19872, hier S. 16.

[75]

Vgl. SUNTROP (2001), S. 18.

[76]

Die Gründung der „Deutschen Luftschiffahrts AG Frankfurt a. M.“ (DELAG) erfolgt

am 16. November 1909.

[77]

ENGBERDING, Dietrich: Luftschiff und Luftschiffahrt in Vergangenheit, Gegenwart

und Zukunft. Berlin 1926, hier S. 239.

[78]

MAYER, MÜLLER-AHLE (o. D.), S. 28.

[79]

Diese Fahrt ist der dritte Versuch, Köln zu erreichen; am 2. bzw. 4. August

musste ‘LZ 5’ wegen schlechten Wetters bzw. eines technischen Defekts

unfreiwillig die Rückfahrt antreten.

[80]

DIETMAR (1991), S. 313.

[81] Vgl. SONNTAG,

Richard: Über die Entwicklung und den heutigen Stand des deutschen

Luftschiffhallenbaus. In: Zeitschrift für Bauwesen, Heft 62, 1912, S. 571–614,

hier S. 599.

[82]

Ein Wettbewerb, der die Gestaltung einer Luftschiffhalle klären sollte, wurde

im Oktober 1908 in Deutschland ausgeschrieben; der Entwurf der

Brückenbauanstalt „Augsburg-Nürnberg AG“ erhält den dritten Preis.

[83]

Vgl. SUNTROP (2001), S. 25.

[84]

SONNTAG (1912), S. 574.

[85]

SONNTAG (1912), S. 574.

[86]

Vgl. Endnote 37. Formal ist die Luftschiffhalle in Bickendorf

durchaus mit der Luftschiffhalle der Firma Clouth von 1907 vergleichbar.

[87]

Vgl. SONNTAG (1912), S. 596.

[88]

SONNTAG (1912), S. 582. Die Dauer des Vorgangs ‘Öffnen/Schließen’ einer

Luftschiffhalle mit maschinenbetriebener Hallenöffnung betrug damals ca. 15

Minuten.

[89]

Vgl. VON TSCHUDI, Georg: Luftschiffhäfen, Ankerplätze und Flugplätze. In:

Deutsche Luftfahrer-Zeitschrift, Nr. 15, Jg. XVI, 1912, S. 361-364, hier S.

362. Eine Auflistung aller bis einschließlich 1912 existierenden

Luftschiffhallen, Flugplätze, Flugfelder und Landungsplätze in Deutschland ist

dort zu finden.

[90] Vgl. SUNTROP (2001), S. 53.

[91] MAYER (2001), S. 15.

[92]

MAYER, MÜLLER-AHLE (o. D.), S. 22.

[93]

Vgl. MAYER, MÜLLER-AHLE (o. D.), S. 22–24.

[94]

Vgl. MACKWORTH-PRAED (1993), S. 140.

[95]

Vgl. Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger, Nr. 494/495, 28./29. Oktober 1909 sowie Nr.

505–507, 4.–6. November 1909; MAYER, MÜLLER-AHLE (o. D.), S. 23; SUNTROP (2001),

S. 34.

[96]

Vgl. KNÄUSEL, Hans G. (Hrsg.): Zeppelin. Aufbruch ins 20. Jahrhundert. Bonn

1988, S. 161.

[97]

Vgl. KNÄUSEL (1988), S. 163. ‘(Ersatz-)Z II’ ist die offizielle

Betriebsbezeichnung des Luftschiffes.

[98]

Vgl. SUNTROP (2001), S.44 u. 52.

[99] Vgl.

Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger, 1. Mai 1912, Nr. 199; MAYER, MÜLLER-AHLE (o. D.), S. 30.

[100]

Vgl. SUNTROP (2001), S. 49. Die Erlaubnis ist an die Bedingung geknüpft, dass

fotografische Apparate nicht mitgeführt werden dürfen. Zudem muss zu jedem

Aufstieg ein Vorstandsmitglied des CCfL anwesend sein.

[101]

VON KLEIST, Ewald: Militär und Luftschiffahrt. In: Wir Luftschiffer, 1909, S.

285–306, hier S. 306.

[102]

Vgl. VON TSCHUDI (1912) S. 362/363. Im Jahr 1911 sind bereits in u. a. in

Straßburg und Metz Militär-Fliegerstationen errichtet worden.

[103]

SUNTROP (2001), S. 65.

[104] TÜRK, Oskar:

Der Flughafen Köln in der Geschichte der Kölner Luftfahrt. In: Deutsche

Flughäfen, Heft 6/7, 4. Jg., 1936, S. 7–15, hier S. 10.

Timeless Aviation?

Clouth Series 1; 1st steerable airship

The first flight objects, which were

created as balloons or as a zeppeline, were initially completely wind dependent,

so wind directions had to be taken into account as part of the launch, if one

wanted to achieve a certain goal. There were therefore no steering possibilities.

Franz Clouth had obviously thought about it and, together with his engineers,

built the first steerable airship, which was still basically wind driven, but in

principle allowed changes in direction by steering. This was made possible not

only by the side-rudder, but also by the engine.

The Franz Clouth balloon factory in Cologne built a small airship, which was

exhibited at the ILA (Internationale Luftfschiffahrts-Ausstellung) in Frankfurt

am Main in 1909.

It could be quickly assembled and dismantled, so it seemed to be very useful for

military purposes. Apart from guides and machinists it could take four persons

on board, as well as fuel for about 10 flight hours. This model was bought by

clubs and clubs. The airship made its maiden voyage to the International

Air Navigation Exhibition (ILA) in 1909 to Frankfurt and proved its special

maneuverability. At the same time, the hussars were unintentionally stepping

into the streets of Frankfurt and, without suffering any damage or injury, to

pass between the houses, to rise again to their proud heights. Because of this

elegant achievement, the Cloudian airship was called the "family carriage of the

future".

Airship Commander Richard Clouth

(with beard and cap) Forced landing in the streets of Frankfurt

Forced landing while International

Airship Exhibition 1909

The astonishment was

also great when the airship, controlled by Hauptmann von Kleist, appeared on

June 21, 1910, at the International Industrial Exposition in Brussels. It had